Turkey Call Magazine Changed My Life

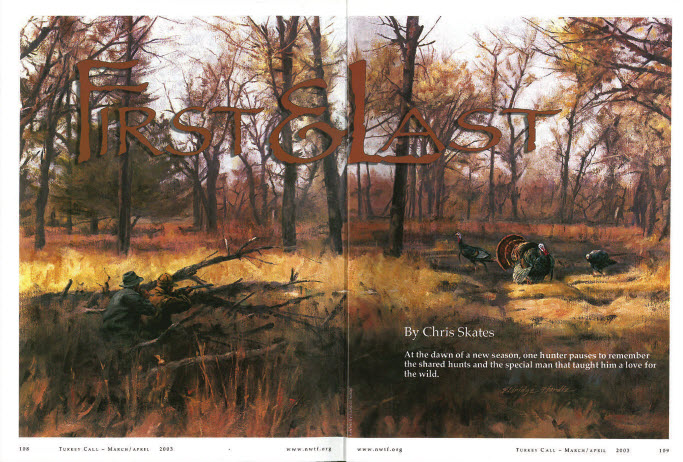

My first published story was entitled “First and Last” and was featured in April 2003 in the 30th Anniversary Edition of Turkey Call magazine.

The National Wild Turkey Federation had been founded in 1973. The story was about how, in that same year, my grandpa (my “Pop”) took me on my first turkey hunt when I was 10, and I took him on his last turkey hunt when he was 93. A perfectly appropriate Eldridge Hardie painting graced the introduction. The story mostly covered our relationship, but it also covered the arc and scope and evolution of turkey hunting up to that point.

That first turkey hunt in 1973 was also during the first legal turkey hunting season in Georgia in decades. In that first season, a wild turkey was an ethereal thing. A gobbler was like a phantom. Forget seeing a turkey, if we just heard one gobble, it was an event worth telling the boys about down at John Junior’s store as we gathered around the old chest Coca-Cola cooler. Most Georgians were deer hunters at the time, so schoolmates laughed when I told them I was going turkey hunting that spring. Not one of them had ever heard of turkey hunting.

Items such as calls, camo and turkey shells were nonexistent anywhere in the state. A Lynch’s Jet Slate ordered from the back pages of Outdoor Life and some army surplus oakleaf camo shirts left over from Fort Benning and the Vietnam era were our only specialty equipment. A Ben Lee 45 RPM record was our only instruction.

Pop and I had been preparing for opening day for weeks and built three natural blinds using cedar saplings and oak limbs that were leafing out a bit that warm early spring. The only tactic we knew was for each of us to get in those blinds 200 yards apart, scratch three yelps on our Jet Slates and then sit the call down for half an hour. In all honesty, it worked about as well as all the “runnin’ and gunnin’” that I fell in love with through the late 80s and early 90s. I killed a 2-year-old gobbler that first year shooting a 20-gauge single shot. Such a shotgun was later deemed to be wholly inadequate and nearly unethical but is now back in style, albeit with modern chokes and loads.

I moved to Kentucky in 1994 and killed two gobblers in the first two days of my first Kentucky season. The second one was a grand ol’ limbhanger I got to work for three solid hours before pulling the trigger. My Pop died the following year. Turkey hunting has been a huge part of my life and by far my number one recreational pursuit since that first hunt 49 years ago, but back to writing.

It is difficult for me to put into words the impact that having that first article published in Turkey Call had on me. It is no overstatement to say it totally transformed my life. Once I had that first article published, I knew I could fulfill a lifelong dream of being a writer. I have since published over 200 articles in dozens of different outlets. Though I often regret it, my writing led me away from outdoor writing to a paid technical writing gig, to political commentary, to a gubernatorial appointment as a chief speechwriter, to being appointed as an advisor to the United States secretary of energy. One downside, as my service in Washington took off, my time to pursue my first love, turkey hunting, diminished.

I nearly lost it all in early 2020. One day on my walk from the Department of Energy Headquarters in D.C., I passed out cold on the sidewalk. I came to and got to my feet with the help of a stranger. I decided I better find a doctor. Two days later, I was told I had Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. And not just any leukemia, the rarest and most deadly on the planet. It had a 98% fatality rate. After massive doses of chemo and radiation, I had to be transferred to Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore for the complete annihilation of my own bone marrow and later a marrow transplant. I lay in isolation at Johns Hopkins hospital in downtown Baltimore. A single exposure to COVID would have been fatal. I would miss the 2020 and 2021 turkey seasons.

A man thinks about a lot of things when he’s lying in a hospital for days on end in what is essentially a small cubicle. Mostly I thought about my wife and family and if I would live to love them longer. But for a couple of those days, I thought about turkey hunting. My view day after day was of some boarded-up warehouses through a grimy window. I could see a bit of the adjoining roof and mostly a huge central AC unit.

I remember vividly one day reliving every one of my turkey hunts. Perhaps it was the state of my health or a bit of depression, but I lingered over the near misses and the screw-ups. Over the decades, there have been plenty of both. I was in and out of consciousness but came to the next morning as the sun rose. I looked at the sliver of sky I could see through that window, and I cried out a prayer to God.

“Lord, am I ever even going to hear another turkey gobble?”

In the grand scheme it was a silly thing to cry over, but I cried quietly and alone. I had lost 65 pounds, I was nearly too weak to walk to the toilet, my hair and beard were gone. I couldn’t eat. I couldn’t drink water some days without throwing up.

By the fall of 2022, my doctor released me to hunt. We have a fall archery turkey season. I was too weak to draw my bow, so I bought a crossbow and went to an old familiar hunting spot (not too far from the truck) with the help of a cane. Normally for fall turkey hunting, I stick with soft clucks and purrs, but after being out of the woods for nearly three years, I couldn’t resist.

I’d taken that same old Jet Slate along for the nostalgia of the thing, and, instead of quiet clucks, I let loose with a series of loud yelps and a cackle. I didn’t care, I just wanted to call loudly because I could. One hundred yards away, an old tom did what he wasn’t supposed to that time of year either: he hammered a gobble. Then he gobbled again, and again.

At first, I sat there stunned. And then I remembered that hospital prayer and it was as if, God said, “Yes, you’re going to hear one gobble again.”

Such a direct answer from the Almighty is a powerful thing, so the sobs snuck up on me, then overtook me. Ultimately, the old gobbler went the other way, up the bluff and not down into the valley where I was. No matter. I’d just experienced one of the best hunts of my life.

It seems we are in an era where everything in life is changing too fast and not for the better. I have lived through almost no turkeys in the South and a virgin hunting season for a state to an abundance of turkeys. I have hunted from three soft yelps on a slate to loud runnin’ and gunnin’ cuts on a quad reed mouth call. A few years ago, I went back to soft yelps on a slate again because the birds in my area have been over-called for years.

Perhaps this year, on my first spring hunt in three years, I will build a natural blind. Perhaps I will yelp softly three times on that Jet Slate and sit the call down for half an hour. Perhaps turkeys will be ethereal things once again and hearing one gobble will be an event. But what an event it will be. I’ll be alive. I’ll be in the Southern spring woods once again. And somewhere through the mist will be that ol’ tom to match wits with.

Chris Skates is a freelance writer, former chemist, outdoor writer, political commentator, speechwriter and advisor. Most importantly, though, he is a long-time turkey hunter.