The Gobbling Chronicles

The science of gobbling chronology plays an important role in understanding hunter satisfaction and the biology of wild turkeys.

There are an estimated 2.5 million turkey hunters in the U.S. who love to hear a turkey gobble. A roosting tom’s thunderous gobble summoning hens on a spring morning is what excites them most. Even more, being mere yards from a shimmering sun-dazzled strutter’s super-charged gobble can jolt the strongest of hearts into wild hammering, and humble seasoned hunters into breathless wonder. Little surprise wild turkeys are a valuable public wildlife resource and beloved by hunters and nonhunters alike.

State agencies are charged with regulating hunting seasons toward a goal of maintaining high-quality hunting while allowing turkey populations to increase. In recent years states including North Carolina, Louisiana, Georgia, Texas, Arizona, South Carolina and Alabama (see sidebar), are using Autonomous Recording Units (ARUs), also called songmeters, to gather gobbling activity and chronology data to achieve those and other conservation-related goals.

North Carolina’s Gobbling Study Certified wildlife biologist Chris Kreh, assistant chief of North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission’s Game and Furbearer Program, offers insight into how the state’s gobbling project uses ARUs.

“Gobbling studies are critical to understanding hunter satisfaction as well as wild turkey biology,” Kreh said. “We saw a huge need to get a better understanding of gobbling activity across the state. We wanted to know how to safeguard the turkeys and also satisfy hunters as much as possible. The North Carolina Chapter of the National Wild Turkey Federation’s initial support made it possible to launch the study and its support continues.

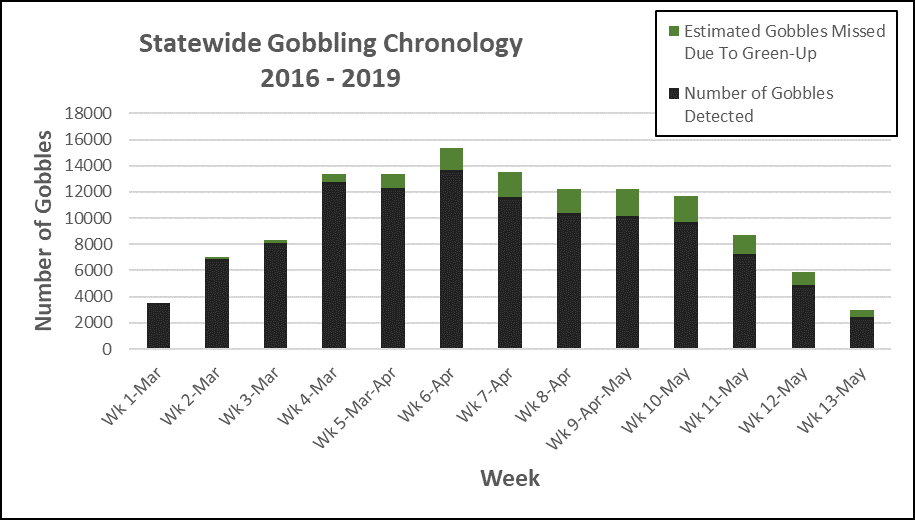

“From 2016 to 2019, our objectives were to test the ARUs, train field biologists and technicians in their setup, collect audio and use associated analysis software to analyze and interpret the data. The results were used to help evaluate the timing and structure of the spring hunting season. In 2020, we began using 51 ARUs to gather gobbling data as part of a larger turkey ecology study in partnership with North Carolina State University, Louisiana State University and the NWTF.”

How ARUs Work

An ARU is a self-contained audio recording device used for bio-acoustical monitoring such as in gobbling chronology studies. The battery-operated units record audio files onto SD cards. One set of batteries typically lasts for the entire 13-week project. The audio files are then processed using automated software capable of isolating and identifying gobbles. ARUs were first tested to identify factors that might affect their performance at detecting turkey gobbles. Topography and spring green-up were the most notable influencers, but those were accounted for in data analysis. Other impacting factors include wind, background noise, distance and forest type from region to region.

Site Selection and Deployment

“ARUs were deployed at locations across the state with robust turkey populations that receive little to no hunting pressure,” Kreh said. “We really wanted to know what gobbling patterns would be like without influence from hunters harvesting or pressuring turkeys.”

Recorders are housed in security boxes and bolted to trees about 6 feet above ground. Sites where possible theft or prescribed fire may occur necessitate placing them at about 15 feet. The ARUs were deployed from late February through early June and recorded for two-and-a-half hours each day starting 30 minutes before sunrise in deciduous, nondeciduous and open habitats.

Data Analysis Tells the Story

From 2016-19, more than 113,000 gobbles from nearly 54,000 hours of acoustic recordings were counted representing the entire state.

“What we thought we knew about turkeys was that gobbling in the spring showed two very pronounced peaks of activity with one peak occurring just after winter flocks break up and a second peak after hens begin incubating nests,” Kreh said. “We refer to that as a bimodal pattern. What we learned using ARUs is that turkeys didn’t necessarily subscribe to a bimodal pattern when we looked on a regional and state-wide scale.”

The study found that gobbling chronology follows a more complicated pattern with multiple peaks. The North Carolina report suggests that identifying peaks in gobbling activity may not be the ideal way to inform regulatory decisions. A better way may be to examine how much gobbling activity can occur before, during and after hunting seasons. In the study on the nonhunted properties, 25%, 60% and 15% of gobbling activity occurred before, during and after the time when the state’s spring turkey hunting season is open on hunted areas.

North Carolina Gobbling Chronology Study: By The Numbers

113,000 Gobbles recorded between 2016 – 2019 in North Carolina

54,000 Hours of acoustic recordings in a four-year period

25% Gobbling activity before North Carolina’s spring turkey season opened

60% Gobbling activity during North Carolina’s spring turkey season

15% Gobbling activity after North Carolina’s spring turkey season closed

“We want to have confidence that reproduction is going to happen, that the toms are out there breeding and, at the same time, be sure the spring hunting season is at a time that hunters are excited and satisfied,” Kreh said. “There’s a balancing point between these two somewhat competing needs. Gobbling studies combined with the results of ongoing nesting chronology studies will better inform decisions about the best time to open and close spring hunting seasons.”

ARUs hold tremendous potential for wildlife research and management, especially wild turkeys and other game birds such as bobwhite quail. They offer the opportunity to survey for vocalizing birds over much greater time spans than can be achieved using traditional human-based observers. ARUs reduce potential bias associated with multiple human observers and eliminate any pressure caused by the presence of human observers carrying out surveys.

Partnerships and Funding

The study is funded by the NCWRC, the Sport Fish and Wildlife Restoration Program and the NWTF North Carolina State Chapter. First year costs totaled $52,500 due to the purchase of the ARUs, security boxes, accessories, etc.

The North Carolina Chapter provided $51,429 during the first three years of the project allowing the remaining costs to be drawn from the Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration Program (Pittman-Robertson Funds). Data analysis and interpretation was made possible by a partnership with North Carolina State University.

“NWTF’s initial financial support of the gobbling chronology study really helped launch the project,” Kreh said. “Over the course of 2016-19, more than $250,000 was spent. If we collected the same amount of data using biologists and technicians in the field each day listening for gobbling turkeys, the cost would likely have exceeded $6 million … although that probably would have been more fun.”

The field work for this project is the product of numerous NCWRC biologists, including Kreh, and technicians. Additional support and cooperation were provided by North Carolina Parks, North Carolina Forest Service, North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Boy Scouts of America, North Carolina Zoo, Orange County Water and Sewer Authority and numerous private landowners.

Gobbling research, such as this completed study in North Carolina, continues to be an integral part of ensuring a bright future for turkey hunting and management.