Home, At Last, Is the Hunter: A 30-Year Perspective

The second Monday of the Ohio spring turkey hunting season, May 5, 1986, will be riveted in my memory forever. It was the day I was shot.

That quote began a feature story titled “What I Lost” in the November-December 1987 issue of Turkey Call magazine, graphically describing the turkey hunting accident I was involved in on that date at Mohican- Memorial State Forest in Ohio.

“I was hit with approximately 20 No. 4 lead pellets from a distance of 30 yards,” the story continued. “Shot penetrated my left upper arm, shoulder, neck, head and side of the face. The worst of my injuries, though, was a pellet that went completely through my left eyeball. After three surgeries, I permanently lost the sight in that eye.”

During the years following that mistaken-for-game incident, I wrote several similar stories for other national outdoor magazines. In addition, I spoke to numerous hunters at firearms safety classes, conservation clubs and church game dinners, preaching turkey hunting safety. It was during those years it became apparent that I had much more I wanted to say about this turkey hunting life we all love. But I wanted to do so in the form of a true rarity in turkey hunting literature. I wanted to create a full-length fiction novel based on actual events, my accidental shooting included.

Over time, the various characters and setting for the book gradually began falling into place. I started the actual writing in an old farmhouse near Glady, West Virginia, adjacent to the Monongahela National Forest, pecking away on a portable typewriter. Some buddies and I rented that farmhouse for a week each spring to turkey hunt its surrounding mountains. It was that small farm and its nearby remote forest trails that became the setting for the story.

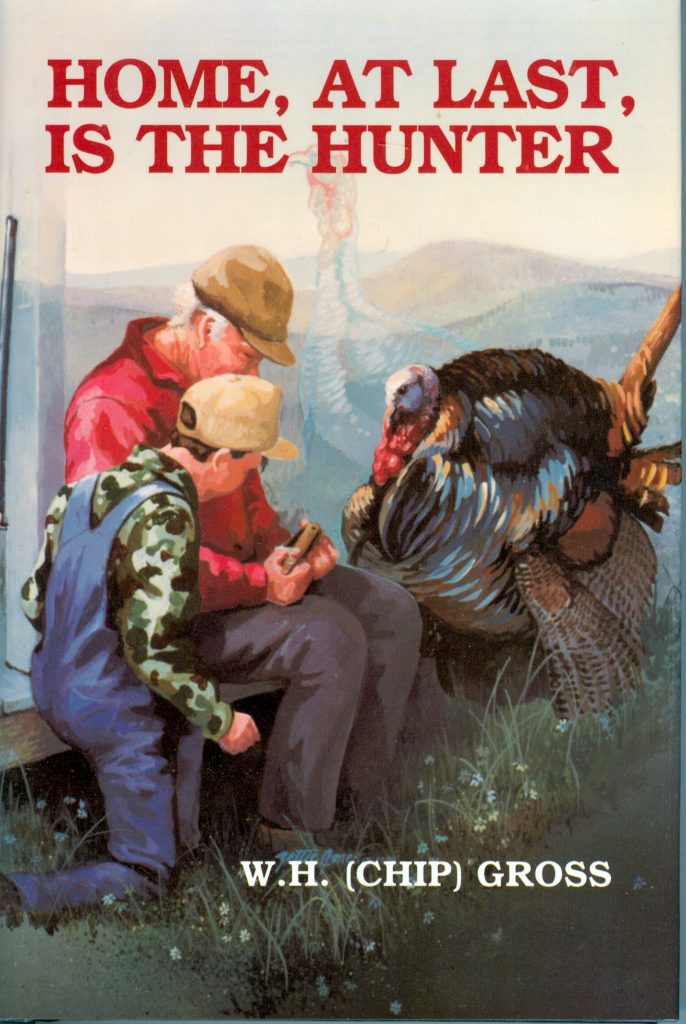

In brief, it’s the tale of a young boy, Jeff Stewart, who learns to hunt the wild turkey from his maternal grandfather. A timeless story, the book follows Jeff from ages 12 to 21, chronicling his many adventures in the turkey woods spanning those formative years. It’s during that time he not only matures as a turkey hunter, but also grows mentally, physically, relationally, even spiritually, while simultaneously being forced to face one of life’s most monumental struggles: death.

The grandfather in the book, known as The Boss, is a combination character, made up of the two men in my life who taught me the most about the outdoors as a kid, my father and grandfather. Another prominent character, a state wildlife officer, is also a combination character, made up of several wildlife officers I have known. After four years of writing, Home, At Last, Is the Hunter was finally completed and published in 1994, marking this year, 2024, as the book’s 30th anniversary.

I won’t spoil the story by giving you any more details, but it’s safe to say the book has been read and enjoyed by thousands of younger and older turkey hunters alike. Young people seem to relate to Jeff’s many challenges and victories in the woods, while older hunters empathize with The Boss in his attempts to gently, yet wisely, mentor his grandson.

Answering the question as to what I lost as a result of my turkey hunting accident is difficult to describe, and multilayered. It was more than just an eye. It was also the loss of the total freedom and enjoyment that turkey hunting can offer. Before the incident, there was never a thought in my mind that my next hen call or next step in the woods could be my last. Now, the complete exhilaration the sport once provided is tarnished a bit. Never again will I be able to walk carefree through the woods as I did before. There will always be a shadow of fear and caution surrounding turkey hunting for me. That feeling has diminished in intensity through the years, but it still lingers.

I also learned that experiencing trauma exposes life’s priorities, sometimes very quickly. When the man who shot me pulled the trigger on his shotgun, and seconds later I figured out what had happened, my first thought was of God. Bleeding heavily yet not knowing how seriously I was injured, I reasoned that I might be seeing Him very soon. As a result, I said the shortest yet most urgent prayer of my life, “Jesus, Help!” My next thought was of my family; my wife, Jan, and our two young sons, both still in grade school at the time. The thought that I might not see the three of them again was overwhelming. The many years since the accident have given me much time to reflect not only upon my decades as a turkey hunter, but also upon life itself. Most young people believe they are invincible, “bulletproof” would be an ironic yet accurate description. Bad things always happen to someone else. But at age 34, I found out differently, and it’s made me appreciate the blessings of life more deeply. I take nothing for granted anymore: my wife, children, seven grandchildren, and as I grow older, my health. Every day is a gift from God, and as a result I try to live for Him and serve Him the best I can.

I didn’t turkey hunt for four years following the accident. I just felt too uncomfortable in the woods. And when I began hunting again, I no longer employed the same run-and-gun technique I did before. Rather, I now hunt exclusively from a pop-up ground blind, a safer arrangement that allows my mind to relax and enjoy the moment.

I also don’t pull the trigger much these days. Instead, I enjoy photographing and scouting wild turkeys preseason, then calling birds for my grandsons once the hunting season begins — again, from a ground blind — allowing them to experience the thrill and excitement of taking a strutting spring gobbler. In essence, I’ve now become The Boss, and that’s as it should be.

Something to Consider…

You would never go to a shooting range to site-in your turkey shotgun or other firearms without taking along the proper eye and ear protection. So why would you even think of stepping into the turkey hunting woods without the same safety equipment? Had I been wearing shooting glasses or safety glasses the day I was shot, those lenses would have very likely deflected the shot pellet that penetrated my eyeball, ultimately resulting in the loss of sight in my left eye.

Hearing protection while hunting is just as important as eye protection, as hearing loss can occur over time or as the result of a single, excessively loud incident.

“The threshold noise level at which damage begins occurring in the human ear is 85 decibels,” said Anne Jenkins, an audiologist practicing in Columbus, Ohio. “A 12-gauge shotgun produces around 150 decibels of sound. Length of time can play a role, too, as hearing loss/damage is cumulative.”

Electronic ear protection is an excellent choice for preventing hearing damage, as these devices allow you to hear normal conversations at the shooting range and natural sounds while hunting — such as the gobble of a wild turkey — yet they mute the blast of a firearm. — C.G.