Fall Turkey Hunting In The Crosshairs: Will Canceling Autumn Seasons Help Turkeys?

As state agencies respond to declining bird numbers, turkey hunting’s “second season” is coming under fire in some quarters.

Turkey hunting has long been a two-season activity in many areas, but that mindset might be waning. As turkey populations in some parts of the country continue to decline, a few state agencies have responded by curtailing, suspending or canceling fall seasons, which typically allow hunters to harvest any turkey, not just gobblers. That’s prompted approving nods from many folks who eschew killing hens. But it’s spurred questions from others, as some wonder why the changes were made and question the potential effects they might have on those states and others, and the overall fall turkey hunting tradition. The answers, as with any wildlife population dynamic, are anything but simple.

What’s Happened — and Why Reining in fall seasons is nothing new. In recent years, Tennessee, Ohio, Nebraska, Arkansas, Pennsylvania and North Carolina have closed or cut back on autumn turkey hunting. In Spring 2023, Kansas and Mississippi joined those ranks.

The Kansas Parks and Wildlife Commission voted in April to suspend the state’s fall turkey season. Officials say Kansas’ turkey population has been decreasing for about 15 years, dropping about 60% from 2008 through 2021. Further, the number of fall turkey hunters in the state has decreased substantially since 2015, declining by about 20% per year.

“KDWP staff view the ability to reduce or eliminate harvest during the fall season as an important tool in our overall strategy to appropriately manage turkeys in Kansas,” said Kent Fricke, small-game coordinator for the Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks. “New research projects will help us better understand the potential impacts of harvest on turkey populations, as well as the interactions of harvest with other variables affecting turkeys, including weather events, habitat quality and quantity, and disease.”

In May, Mississippi took a similar step, as the state’s Commission on Wildlife, Fisheries and Parks canceled the state’s fall turkey season. Several years earlier, the state had partnered with Mississippi State University to build a turkey population model. It indicated that increasing the fall and winter survival rate of female turkeys could result in overall population growth.

“I am not insinuating the limited hen harvest we had was the root cause of our problems,” said Adam Butler, wild turkey program coordinator with the Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Parks. “However, given the sensitivity of the population to female survival, we felt disallowing hen harvest to be a rational best management practice when considered alongside the objectives of the overwhelming majority of our hunters.”

It remains to be seen how eliminating fall harvests will affect turkey populations in Kansas and Mississippi. However, overall public reaction to the changes in those states has been mild.

“The majority of spring hunters have been in favor of reducing or removing the fall season, while active fall participants have wanted to keep the opportunity,” Fricke said. “The majority of feedback KDWP has received has been indifferent to positive, but there are some hunters who would like have seen the fall season continue.”

Butler said Mississippi’s fall season offered minor opportunity, as it was less than two decades old, only open in 24 of the state’s 82 counties and only on private land. Responses to a 30-day comment period on the change supported the decision.

“We had a relatively high response rate from the public during the 30-day period, and 83% of the public comments we received supported our recommendation,” he said. “This was in line with what we’ve seen before. In all our past opinion polling going back decades, Mississippi turkey hunters have been strongly opposed to allowing turkey harvest outside the traditional spring season.”

The Biological Give and Take

The main issue with fall seasons, of course, is killing hens — especially in areas where turkey numbers have dwindled. On the surface, it seems logical that sparing hens could have a positive effect on overall populations, and research backs that up. For example, a Virginia study (McGhee et al. 2008) concluded, “Over the range of fall harvest rates, expected spring harvest maximized at a fall harvest rate of zero and declined as fall harvest rate increased.” A Pennsylvania study (Casalana et al. 2005) said, “Closing the fall turkey hunting season on the study area may aid in population growth if hen survival increases as a result.” And a study in Virginia and West Virginia (Pack et al. 1999) said, “Our results suggest a wildlife agency only consider a spring season if the desire is to achieve maximum growth rate of the wild turkey population and maximum spring recreation.”

Further, recent studies (Nelson et al. 2022, and Byrne et al. 2022) suggest that a relatively small number of hens are responsible for most reproduction in many areas, so removing a socalled “super hen” from the population could have a big impact.

Patrick Wightman, post-doctoral research associate with the University of Georgia’s Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, said management such as trapping and habitat improvement can boost turkey production. But without broad-scale — that is, state-level — changes in production, any harvest of female turkeys could potentially be negative.

“I believe this is why you are seeing decreases in fall hunting seasons, because it is what agencies can control at a broad scale,” he said. “Plus, there seems to be a decline in the number of people wanting to hunt in the fall [and] harvest females.”

However, the autumn turkey hunting tradition runs deep in many regions, and although participation might have declined in spots, it remains solid in others. So essentially, fall seasons represent a balancing act between maximizing recreational opportunity and maximizing productivity. Butler said that’s why Mississippi’s decision to halt fall hunting made sense there but cannot be applied to other states.

“Each state has to balance that,” he said. “I don’t think Mississippi turkey hunters and what they want should be applied to hunters elsewhere. It does not fit within our management strategy because it does not fit with our hunters. They’re not willing to trade opportunity in fall for fewer gobblers in spring. But in other states, it seems like hunters would make that tradeoff.”

So state agencies must weigh recreation versus productivity when making tough choices about fall hunting.

“Those decisions will be made by weighing values specific to the culture,” Butler said. “I think it was right for our state but not every state. Decisions about fall either-sex seasons — and all hunting seasons, for that matter — are just as much about sociology as biology. Science can reveal to us the impacts of certain harvest management decisions, but the wisdom of those decisions can only be judged against human values. On this particular subject, people value opportunities around fall either-sex seasons very differently throughout the country. These differences in values will naturally result in different policy conclusions from state to state.

“I personally think it would be a great travesty if fall turkey hunting were lost in those places where it is deeply culturally entrenched.”

Conclusion

Time will tell whether other states cut back or cancel fall seasons, and perhaps research will reveal whether such efforts have positive effects. Meanwhile, the issue is sure to remain divisive, with some concerned hunters applauding any efforts to bolster turkey numbers and traditional fall turkey hunters perhaps fighting to keep their sport alive.

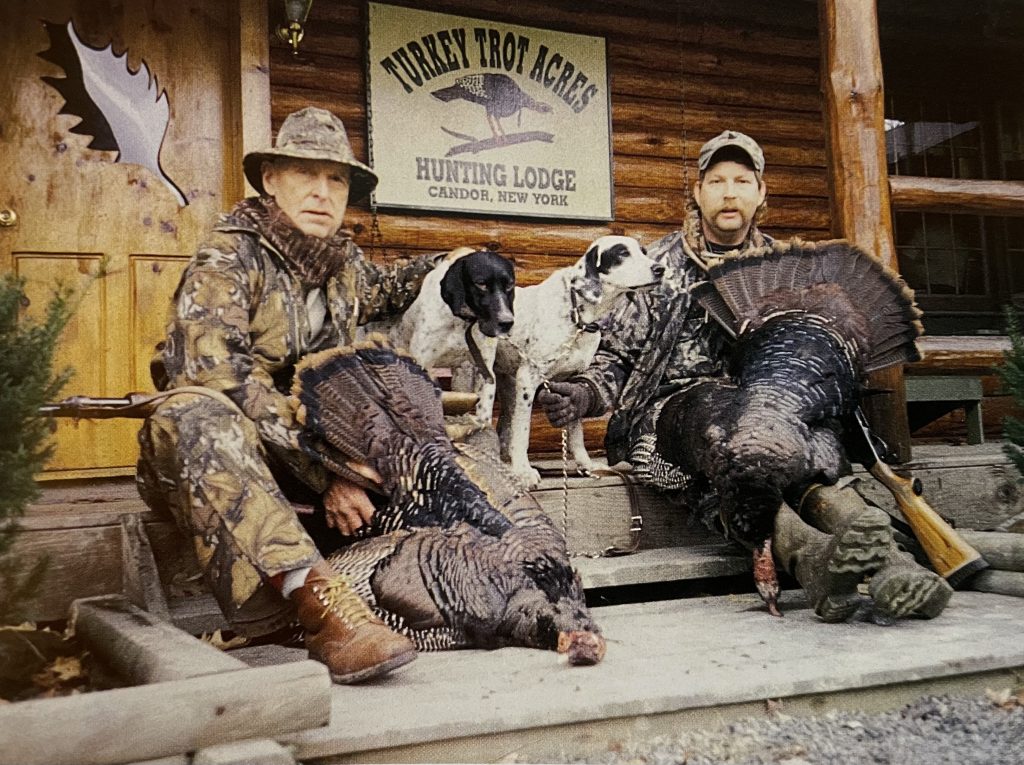

A Die-Hard’s Plea to Save Fall Hunting

Marlin Watkins, a renowned call maker and avid fall turkey hunter from Ohio, doesn’t buy the recent attitude change about fall hunting. In fact, he maintains that fall harvests, including hens, don’t harm turkey numbers, and that autumn hunting is a grand heritage that should be continued.

“Until turkeys were reintroduced to many parts of the country, there was never a spring season,” he said. “Wildlife personnel and hunters thought it was a mortal sin to hunt a lovesick gobbler in the springtime. The tradition of fall hunting ran deep in states like Pennsylvania, Virginia and South Carolina. To me, it’s traditional turkey hunting — the way it always was in years past. There is no sex drive involved, and it’s a hunter against his prey. If one can’t convince a turkey that he is another of their own kind and gender, he will not be successful. No blinds, no decoys — just a hunter with a call and a gun; true turkey hunting to the end.”

Watkins believes much of the push to eliminate or reduce autumn seasons is because of jealousy from spring-only hunters. And he stressed that changes to fall regulations or limits must originate from scientifically based wildlife agencies, not feelings, politicians or popular opinion.

“We as fall hunters, because it is not a popular sport, do no damage to turkey populations,” he said. “In most states, the hen kill is less than 1 or 2%. This harvest has no effect on turkey populations. State wildlife agencies that understand this have fall turkey seasons. If you look at some of the most liberal states for fall hunting, those same states have some of the best turkey populations in the country. It would truly be a shameful world if the tradition of fall turkey hunting is destroyed by feelings and not biological reasoning. We really need to maximize recreational opportunities, not reduce them. Our youth are our hunting heritage future, and fall turkey hunting is a great way to introduce a youth to hunting.”