Colt Forest Stewardship and Timber Transport Pilot Project

Expediting forest restoration efforts in Northern California in an area impacted by a stand replacement fire.

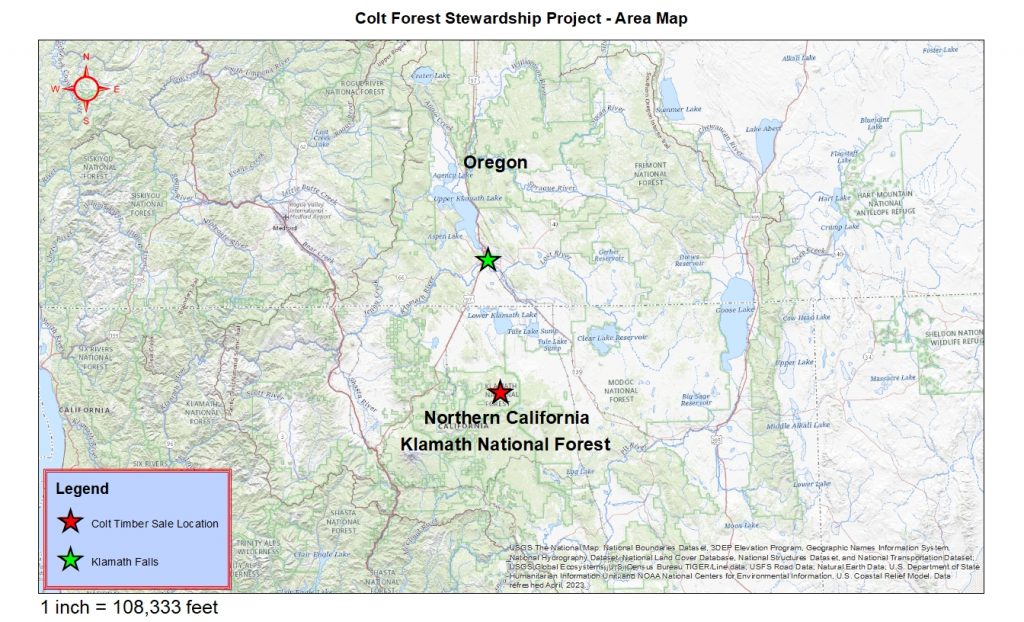

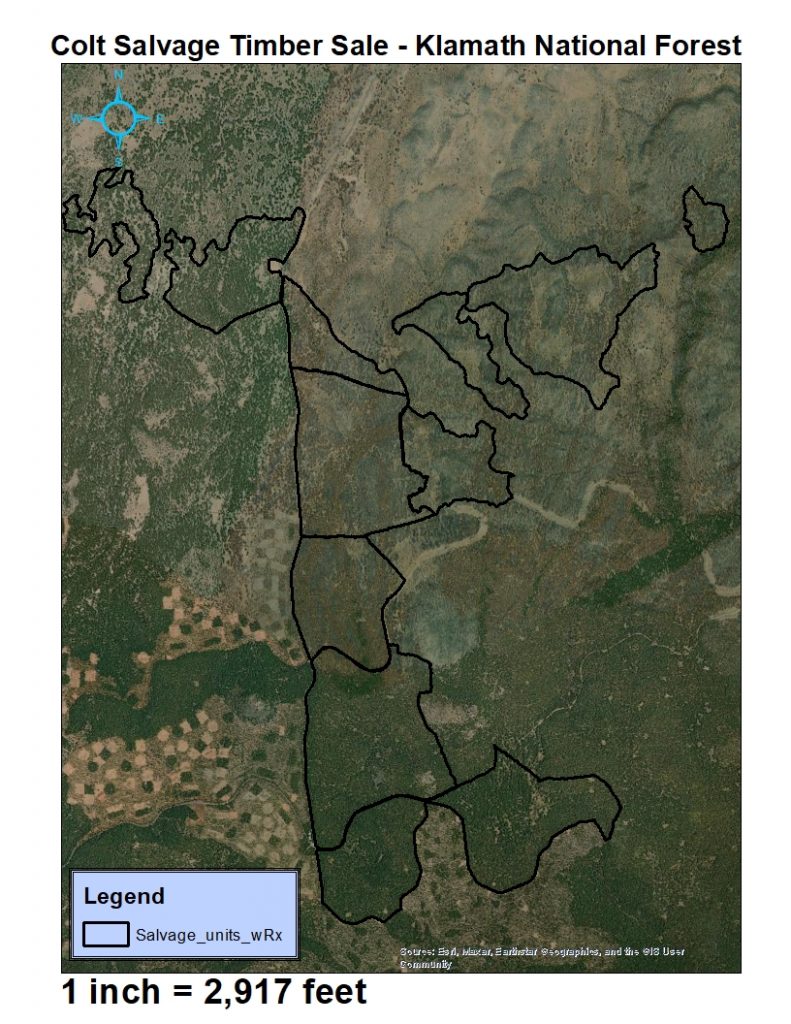

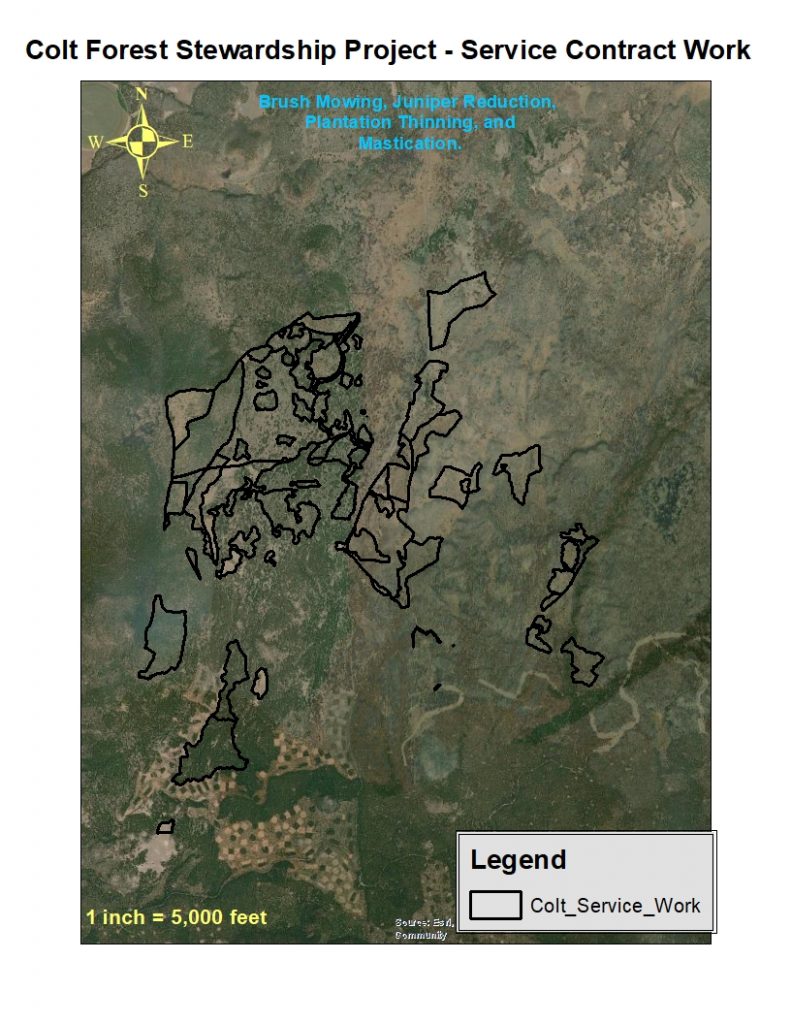

In the spring of 2023, the National Wild Turkey Federation partnered with the United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service to complete the Colt Forest Stewardship Project (Colt) on the Goosenest Ranger District of the Klamath National Forest in Northern California. A majority of the stewardship project entailed a salvage timber sale that burned in the Antelope Fire (145,632 acres) in 2021 and was considered a stand replacement fire, meaning the fire burned so hot that it destroyed most of the area's trees. Other work completed in the project included thinning non-merchantable plantation forested stands, brush mowing, juniper reduction and mastication. Altogether, approximately 6,000 acres of work was completed to enhance wildlife habitat, improve forest health and reduce wildfire fuel loading

Antelope Fire background information: https://www.fs.usda.gov/inside-fs/delivering-mission/excel/employee-perspective-saving-klamath-firsthand-account-antelope

The salvage timber project is being implemented under the Wildfire Crisis Strategy as a Timber Transport Pilot project. The Timber Transport Pilot is being tested as a method of transporting sawlogs from areas of excess supply to areas with sawmilling infrastructure. The goal is to expedite forest restoration efforts in the western U.S.

This project is a part of the 20-year National Master Stewardship Agreement the NWTF has with the Forest Service. Goals of the Wildfire Crisis Strategy are restoration, conservation, and enhancing wild turkey habitat and wildlife habitat in the western forest landscapes.

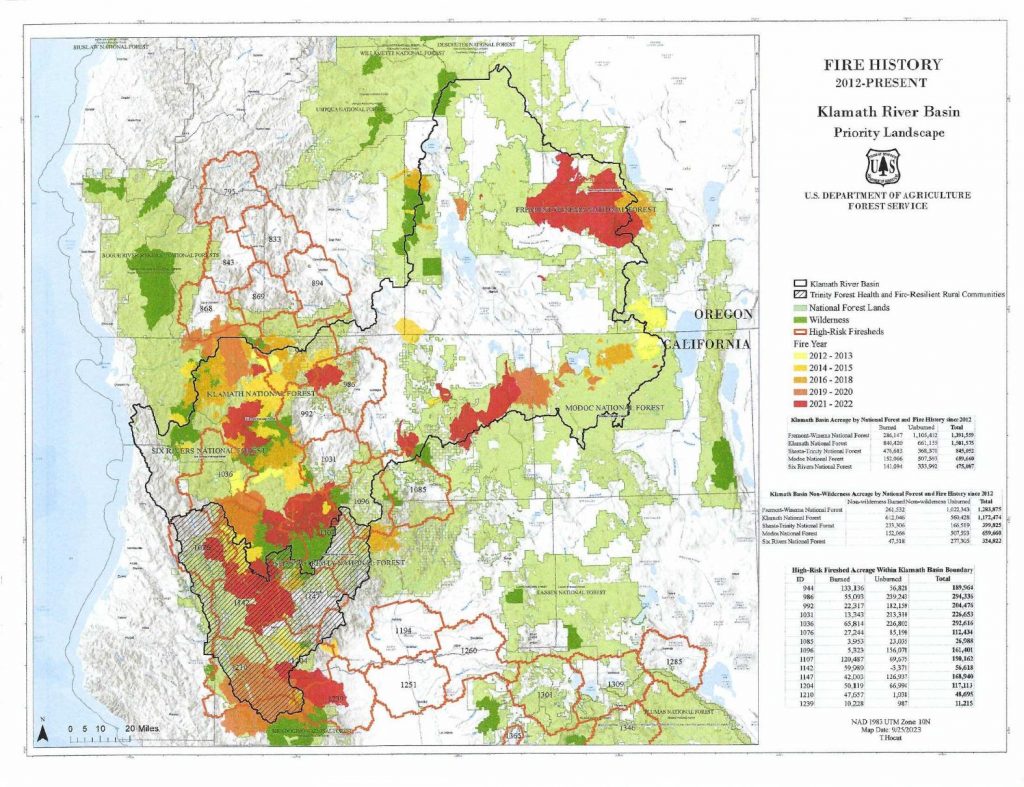

Colt is in the Klamath River Basin, which is identified as a priority landscape in the Wildfire Crisis Strategy. The Forest Service manages 55% of the 10 million acres in the priority landscape. This landscape is at high risk for high severity fires. Nearly 1.9 million acres have burned from 2012 to 2022 within Forest Service lands alone in the Klamath River Basin landscape.

What is the Wildfire Crisis Strategy?

The Wildfire Crisis Strategy (WCS) is a Forest Service strategy funded by the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. The WCS identifies priority landscapes that are mapped into firesheds. Firesheds are delineated based upon where fires ignite and are likely to, or not to, spread to communities and exposed buildings. These areas are located where wildfire poses immediate threats to communities and infrastructure.

Overgrown forests, a warming climate, and a growing number of homes in the wildland-urban interface, following more than a century of rigorous fire suppression, have all contributed to what is now a full-blown wildfire and forest health crisis.

For more information on WCS: https://www.fs.usda.gov/managing-land/wildfire-crisis .

WCS Goals

- Treat 20 million acres on National Forest System lands.

- Treat 30 million acres on additional federal, state and private lands.

- Develop a plan for maintenance on these lands.

Map of Priority Firesheds: Red indicates high priority areas. Orange indicates additional firesheds for treatments. Polygons with no color are National Forest System lands.

EDW FireshedRegistry - Map of Priority Firesheds. This map is interactive.

Why is the National Wild Turkey Federation interested in the WCS?

The NWTF has a 40-year history of partnering with the Forest Service to complete conservation work on the ground. This history and the NWTF's growing concern about issues impacting the western landscape makes it clear that the organization must be involved in these restoration efforts.

The NWTF has a 40-year history of partnering with the Forest Service to complete conservation work on the ground. This history and the NWTF's growing concern about issues impacting the western landscape makes it clear that the organization must be involved in these restoration efforts.

- Clean Water

- Healthy Forests and Wildlife Habitats

- Resilient Communities

- Robust Recreational Opportunities

Management actions implemented through WCS will lead the way for clean water, healthy forests/wildlife habitat, resilient communities and robust recreational opportunities. The NWTF supports the goals outlined in the WCS because these actions are a benefit to wildlife and to communities in the west.

For more information on the NWTF's mission and four shared values: https://www.nwtf.org/content-hub/what-are-the-nwtfs-four-shared-values .

What is the Timber Transport Pilot Project?

The Timber Transport Pilot Project (TTP) is a pilot project to examine the feasibility of transporting wildfire fuels from oversupplied areas in the West by using intermodal transportation systems to forest products mills that need additional timber supply. Intermodal transportation (multiple methods) can be defined as using barge, rail and truck transport to move forest products from one location to another. The project provides transportation infrastructure needed to transport logs from areas of excess supply with limited markets to areas with sawmilling infrastructure. TTP is being tested to increase pace and scale of restoration and maintain critical sawmilling infrastructure necessary to complete forest restoration cost effectively. This pilot project is also beneficial to the Forest Service and industry by invigorating local communities and economies that are sometimes economically challenged.

For more information on TTP: https://www.nwtf.org/content-hub/work-for-the-timber-transport-pilot-commences

Why Colt was recommended for the Timber Transport Pilot Project?

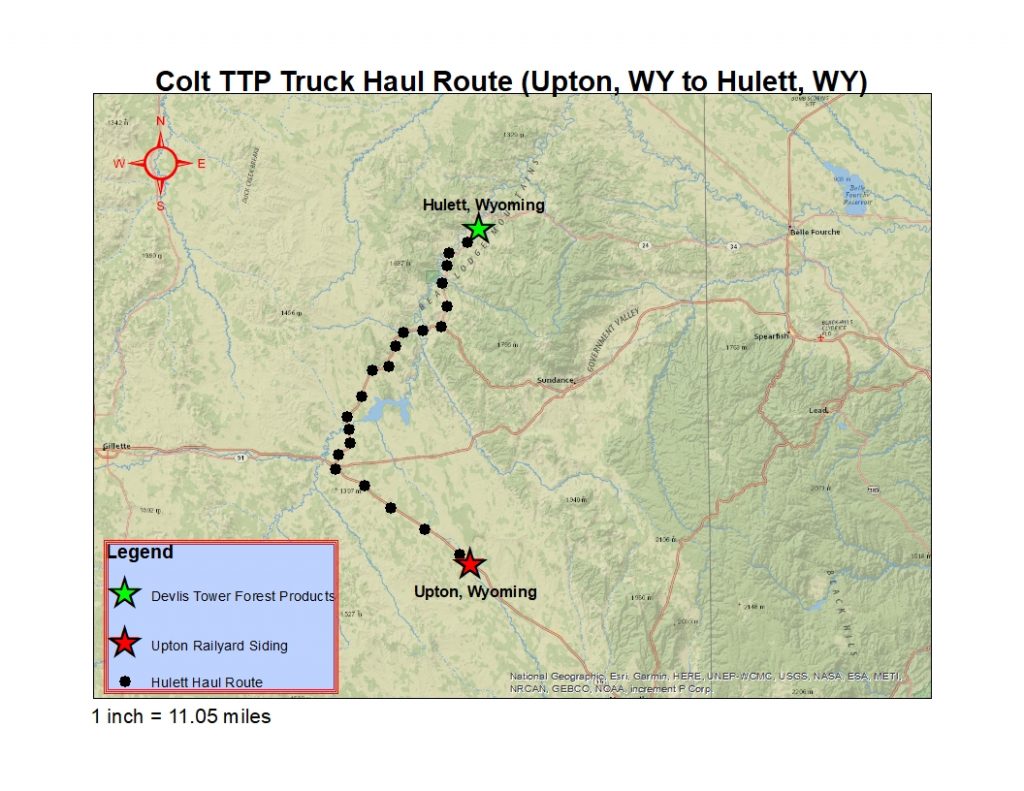

Due to the numerous fires that impacted California during 2020 and 2021, there was an excess supply of fire-killed timber that needed to be harvested. Sawmills in Northern California had limited capacity to accept blackened trees because the timber industry was at full capacity harvesting its own burned trees. Also, ponderosa pine is not a preferred species for many sawmills to use for feedstock. Devils Tower Forest Products located in Hulett, Wyoming, was facing a log supply shortage and needed additional inventory. The Wyoming sawmill only uses ponderosa, so Colt was identified for TTP as a means of expediting restoration on the charred landscape.

Expediting Restoration

The Antelope Fire was a stand replacement fire composed of ponderosa pine. Historically, stand replacement fires are not common in ponderosa pine forests. Ponderosa pine forests evolved with low- to moderate-intensity wildfires. Low- to moderate-intensity fire thins the forests naturally, leaving some trees dead and some trees alive and healthy. Ponderosa pine forests generally do not regenerate after a stand replacement fire, creating the need to expedite restoration.

Timber harvesting is a tool to expedite restoration of burned areas. Trees are harvested to reduce fuel loading to decrease future fire severity and prepare for reforestation. The salvage timber sale provided a tool to reduce fuel loading and use the timber resources. Salvage sales have a limited window to be implemented because dead trees start rotting and decaying, which leads to lost economic value.

The timber harvesting component of the project brought revenue into the project, reducing project costs. The NWTF was able to take the revenue generated from the salvage timber sale and invest it back into the project to treat additional acres.

There are many ecological benefits for expediting forest restoration after a disturbance, whether it be from wildfire, tornado or a hurricane. These include:

- Reduced future hazardous fuel loading by removing dead trees that would otherwise be added fuel to another fire.

- Reforestation of the burn scare by planting native tree seedlings and grasses. This will stabilize soils reducing erosion to creeks and streams that are important to our fisheries and drinking water.

- Future forests will sequester more carbon than a burn scar that may not grow back. The forested site will store more carbon than non-forested sites.

- Many species of wildlife are dependent upon a forested landscape for food, shelter, and water. Without restoration efforts, the Colt site may not have a forest for years to come.

The Connection Between Healthy Forests and Clean Water: The Connection Between Healthy Forests and Clean Water - The National Wild Turkey Federation (nwtf.org)

The Role of Active Management in Preventing Catastrophic Wildfires: The Role of Active Management in Preventing Catastrophic Wildfires - The National Wild Turkey Federation (nwtf.org)

Partnerships Lead to Project Success

The Forest Service partnered with the NWTF to accomplish work completed on Colt through a Supplemental Project Agreement (SPA). The SPA gave the NWTF authority to purchase the timber on the salvage sale and contract out service work to complete fuels reduction, thinning timber stands with no commercial value and wildlife habitat enhancement.

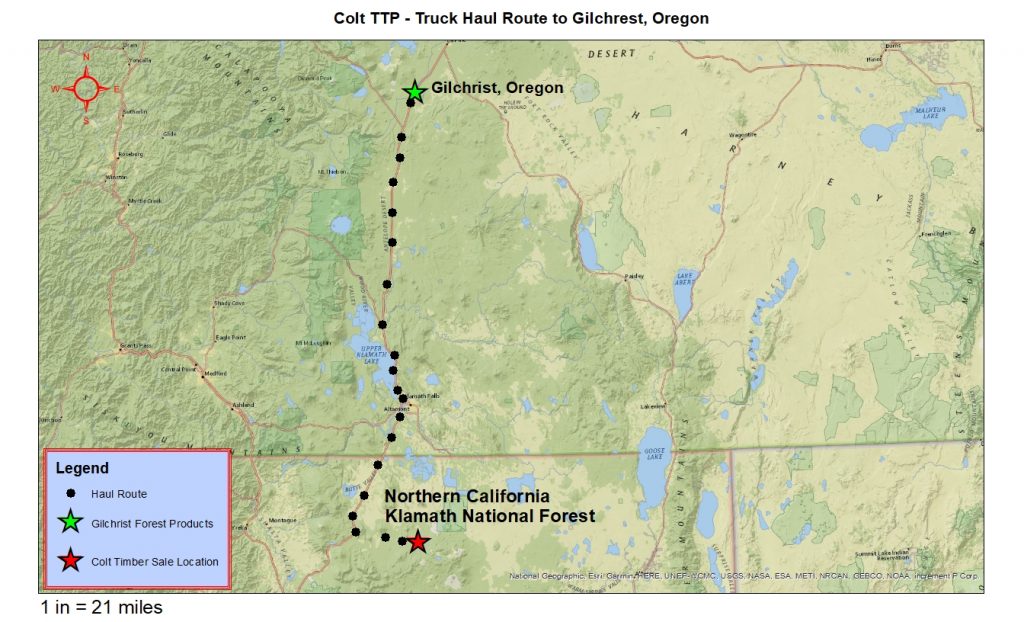

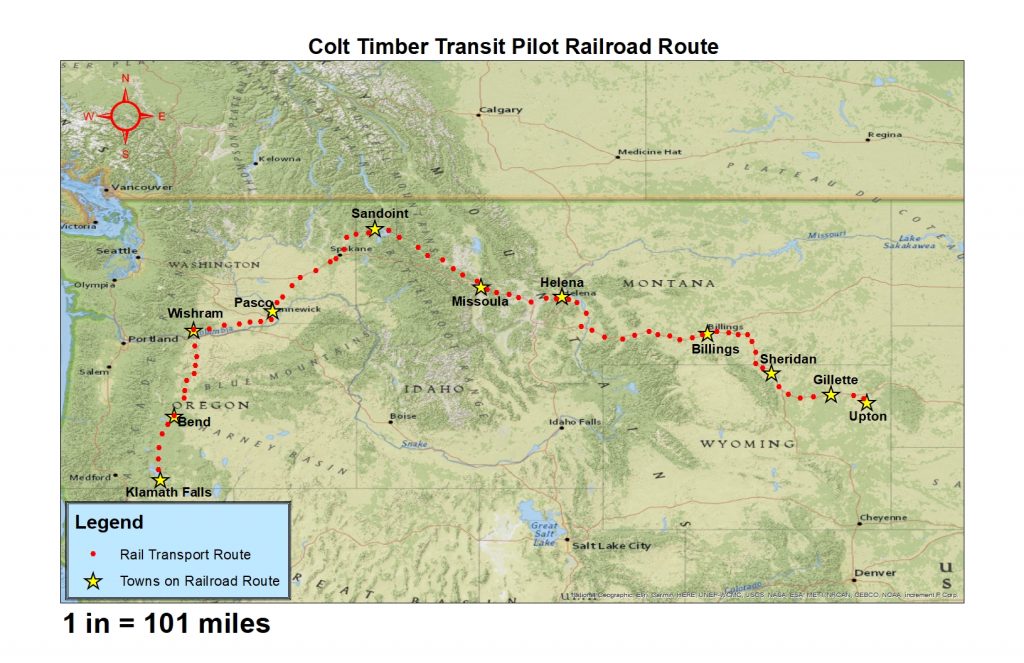

Purchasing the timber allowed the NWTF to multi-stream forest products to different mills that have different needs for log size and species. Because of the short timeline to complete the timber sale, a majority of the pine sawlogs were sold to Devils Tower Forest Products in Wyoming, where they had a need for a large volume of logs. Other mills that bought forest products are Roseburg Forest Products (Roseburg, Oregon), High Desert Lumber Pallet Mill in (Yreka, California), and Gilchrist Forest Products (Gilchrist, Oregon). Multi-streaming forest products added benefit to several companies needing logs and provided the NWTF with the flexibility to complete the timber sale in less than a year.

The NWTF in turn partnered with the California Deer Association (CDA) to manage the Colt Forest Stewardship Project. This partnership is unique because both conservation organizations realized that restoration work needed to be accomplished and would be a benefit to enhancing wildlife habitat, particularly to wild turkey habitat and deer habitat. By partnering to complete restoration work, the NWTF was able to contract with CDA to manage the day-to-day operations of the project.

The CDA was already working on similar projects in the area and was able to expedite the work because of their close location. The CDA is a local conservation organization that has experience managing similar projects in California.

For more information on the CDA: https://caldeer.org/?v=f24485ae434a.

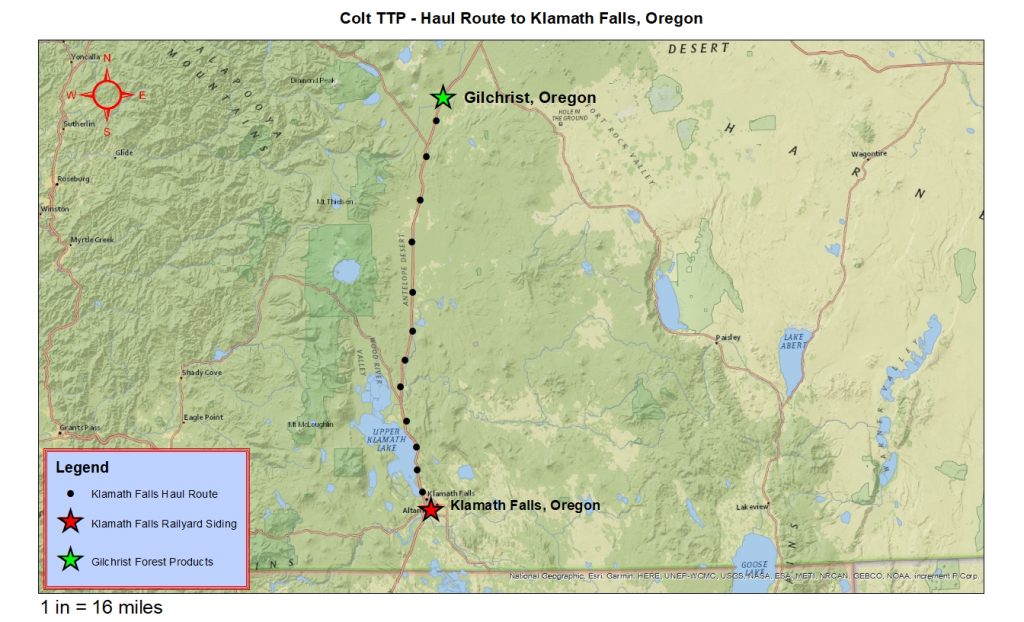

The NWTF and the Forest Service contracted with Forestry First, LLC to transport logs by railcar. Forestry First was a critical partner to this project by supplying the investment in railcar infrastructure and planning and logistical needs necessary to transport logs from Oregon to Wyoming.

The Burlington Northern Railroad was the major rail line used for the transportation. Burlington Northern was able to furnish railcars for log transport. Forestry First had to refurbish and add log bunks to many of these railcars. Most of the railcars used for transporting sawlogs are close to 50 years old.

The True Cost of Catastrophic Wildfire: The True Cost of Catastrophic Wildfire - The National Wild Turkey Federation (nwtf.org)

Timber Transport Pilot Project (Colt Salvage Timber Sale): Trees cut from the stump in California and delivered sawlogs to Devils Tower Forest Products in Wyoming.

The First Phase of Getting Trees from the Stump to the Mill: Timber Harvesting!

Trees are harvested with mechanized logging equipment: these purpose-built machines for logging are a feller buncher, skidder and processor.

The feller buncher harvests the trees and bundles them for skidding.

Work for the Timber Transport Pilot Commences: Work for the Timber Transport Pilot Commences - The National Wild Turkey Federation (nwtf.org)

Next, a skidder with a grapple skids (transports) trees to the landing where trees will be delimbed and processed into log lengths.

Transportation from the forest to the mill

Gilchrist Forest Products (Debarking): Why are logs being debarked?

Logs are being debarked before being transported on rail to prevent the spread of forest insects from California to Wyoming. The insects are native in the U.S. but some forest insects in California are not native to Wyoming. Species of concern: western bark beetle, five-spined ips and California flatheaded borer. These insects can lead to tree mortality and decreased economic value.

The plan to debark logs was a cooperative effort developed by Forestry First and the Forest Service. This process is an added cost, but both entities had concerns about transporting forest insects from one forest ecosystem in California to another forest ecosystem in Wyoming.

Monitoring sites were established in Upton and Hulett, Wyoming, and Spearfish, South Dakota, where the logs were transported. Monitoring protocols were developed by the Forest Service's Forest Health Protection team, and monitoring was completed by the team and South Dakota Department of Agriculture staff. Traps were checked every two weeks. Results from the monitoring indicated no insects from California were transported from this project.

The role of forest management and debarking: Responsible Forest Management: The Role of Debarking in the Timber Transport Pilot - The National Wild Turkey Federation (nwtf.org)

Why logs are transported by railroad and not log trucks to Wyoming?

Railcars are an economical way to transport sawlogs and many other products for cross country transportation. A railcar designed to transport sawlogs can hold up to four log truck loads dependent upon the weight of the load on the railcar. One railcar can hold 16,000-20,000 board feet, whereas a log truck can only hold 4,000-5,000 board feet. Many railcars with logs can be transported by railroad in one shipment. A log truck can only transport one load of logs at a time and is not efficient for long distances.

Another benefit to using the railroad is there is much less carbon emitted in transportation. The 300 miles of trucking with this project puts more carbon emissions in the atmosphere than the 1,400 to 1,500 miles of logs being transported on railroad.

Once the logs are loaded onto railcars, they travel to Upton, Wyoming.

Logs being unloaded in Upton, Wyoming. Photo courtesy of Devils Tower Forest Products.

Logs being loaded onto a log truck with a self-loading log truck. A self-loading log truck is able to load logs without assistance from a purpose-built log loader. Photo courtesy of Devils Tower Forest Products.

Logs are now loaded on the log truck and being transported from Upton, Wyoming, to Hulett, Wyoming, where the logs will be milled. This distance is approximately 60 miles. Photo courtesy of Devils Tower Forest Products.

Logs for the Timber Transport Arrive in Wyoming: Logs for the Timber Transport Pilot Arrive in Wyoming - The National Wild Turkey Federation (nwtf.org)

Above are pictures of the finished product milled in Hulett, Wyoming. These boards are shop-grade material made for windows and doors. Products manufactured are certified by Western Wood Products ( https://www.wwpa.org/) and the harvesting operations are certified sustainable by the Sustainable Forestry Initiative ( https://forests.org/).

Why Transporting Timber by Railroad is Important for Forest Restoration

Forests provide many benefits such as clean drinking water for communities, critical wildlife habitat, carbon banking and sequestration in a warming climate, robust recreational opportunities, and a renewable resource in the form of wood products. Many acres are in high-priority landscapes where rail transport can advance forest restoration. Some of these landscapes are in regions where excess timber supply exists because of no sawmilling infrastructure or a lack of demand for a particular product. The priority landscapes can be characterized by declining forest health conditions and missing one or more natural fire cycles that are essential to naturally managing forests. Ecologically, these areas cannot have fire reintroduced without mechanical treatments (timber harvesting) first. These landscapes are at high risk for megafires (greater than 100,000 acres), potentially converting forested landscapes to open rangelands. Soil erosion in these barren landscapes delivers sediment pollution to the municipal water resources, fisheries and introduces invasive plants to the ecosystem. Wildlife habitat declines and recreational opportunities diminish for many years to come. This is where rail transport can be focused to accelerate restoration. Post-fire restoration costs are by far more expensive than forest restoration before a wildfire.

Railroad transportation is used by many other natural-resources-based industries for transportation. The railroad was once a key partner to the timber industry for delivering sawlogs to sawmills. This age-old concept now has a place again for forest restoration practices. Without railroad transportation there are millions of acres of forestlands that will go untreated because of the shortage of nearby sawmills. Railroad transportation is a time-tested and proven model of business. Railroad transport now needs to become a new model of business for forest restoration in the West.

Colt shows what can be accomplished when combining forest restoration with railroad transportation. Colt also proves the importance of partnerships working together to accomplish stewardship objectives at the landscape level.

Benefits of Colt Restoration

- 6,000 acres of restoration was expedited with this project. Benefits include enhanced habitat for wild turkey, deer and many other forms of wildlife, and reducing wildfire fuel loading in the Klamath River basin priority landscape.

- 2,746 acres of forest products were harvested and milled into boards, sequestering carbon. If these dead trees were not milled they would have been piled and burned, emitting more carbon in the atmosphere.

- Reforestation: planted trees will sequester more carbon on the site than if the site was not planted.

- The project footprint has added value for hunting and recreation users to be able to safely hunt and recreate moving forward. Wildlife can now freely migrate and benefit from what would have been an ineffectual burn scar.

- Acres treated under the service work will lead to future wildlife forage that is critical for the wild turkey, deer populations, and also critical to many other forms of wildlife.

CONNECT WITH US

National Wild Turkey Federation

770 Augusta Road, Edgefield, SC 29824

(800) 843-6983

National Wild Turkey Federation. All rights reserved.