Behind The Bird: History And Conservation Of The Osceola Wild Turkey

How much do you know about the Florida wild turkey subspecies?

Slowly, I crept along a two-track lane cutting through the palmettos. Aimed toward a field corner, gobbles suddenly erupted from an island of pine trees about 100 yards ahead, stopping me dead in my tracks. After a quick evaluation, I abandoned my decoys and army-crawled toward the field until I could plainly see the field corner near the pines. I suspected the roosted birds would soon pitch down, so I propped my Benelli shotgun in that direction and waited.

Less than 15 minutes later, a gobbler landed in front of my fiber-optic bead. The morning hunt was practically over before it began. The bird was my first-ever Osceola turkey, and experiencing the unique aspects that Florida’s turkey woods offers was awesome. I also found the Osceola’s subtle yet distinguishable features incredibly fascinating as the sunrise breached the horizon, bringing in another stupendous March day in the Sunshine State.

If you’ve hunted the Osceola wild turkey, perhaps you’re familiar with the nuances. If not, it’s an experience every turkey hunter should seek, given the unique history and location of the subspecies.

History, Range and Status

Florida is the only place in the world to host Osceola turkeys, which is why the subspecies is the most difficult of the four in the Grand Slam for most hunters to claim — demand is high and supply is low. Before my first Osceola hunt, I misconceived that all turkeys in Florida are Osceolas. During the hunt, though, I learned that Florida also supports populations of the Eastern subspecies.

What exactly is the Osceola’s range? Well, the NWTF recognizes turkeys in Dixie, Gilchrist, Alachua, Union and Duval counties, and all counties south of them, as Osceolas. All birds north of these counties are Easterns. According to Ricky Lackey, district biologist with the NWTF, the Osceola’s range has not changed in the last 50 years. Birds near the dividing line might exhibit minimal physical differences, so turkey hunters seeking an Osceola gobbler in its truest form often hunt south of Orlando.

How did the Osceola, originally known as the Florida turkey, get its name? Many different sources note that W.E.D. Scott was first to formally refer to the bird as “Osceola,” named after Seminole leader Osceola, in 1890.

Lackey suggested that Osceolas are prospering and offer turkey hunters ample opportunity for harvest.

“FWC (Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission) doesn’t have a population estimate, but the Osceola’s overall status is positive,” Lackey said. “Anecdotally, the population is pretty stable throughout the range. Harvest has been stable for the last four to five years, too.

“Strongholds for the Osceola are in the northcentral part of the state and central Florida between Orlando and Lake Okeechobee,” he continued. “For those interested, FWC has a mapping system on its website called Florida Wild Turkey Model, which rates turkey habitat suitability across the entire state.”

Threats and Conservation

Despite their prosperity, we can’t ignore threats to the Florida wild turkey. There are the obvious nest predators, of course, but human invasion is possibly most prevalent.

“Most likely, the Osceola turkey’s most significant threat is human development and land conversion,” Lackey explained. “Actually, all of Florida’s wildlife and wild lands share in that common threat.”

Nevertheless, Lackey noted that strategic conservation efforts are in place to protect Florida’s wildlife — including the Osceola turkey — and wildlife habitat.

“Florida has a large core base of public lands, which is unique for most eastern states, and there are strong public-land-acquisition and conservation-easement programs designed to combat some of the development loss (i.e. Florida Forever),” he outlined. “Additionally, Florida has a strong prescribed fire effort, which is used to effectively maintain wildlife habitats and protect from catastrophic wildfires.”

Lackey also discussed the important role that the Wild Turkey Cost-share Program, founded in 1994, plays in Florida’s conservation.

“This is an almost 30-year cooperative effort to improve wild turkey habitat on public lands throughout Florida,” he said. “Many partners are involved (i.e. state, federal, water management districts, etc.). In the last 10 years, this program is responsible for delivering more than 800,000 acres of improved wildlife habitat on publicly hunted lands in Florida.”

What You Can Do

While there are many different conservation efforts in place designed to support the Osceola, much of it is focused toward public lands. For that reason, landowners must address conservation on an individual level and practice positive land stewardship.

“Landowners can and should educate themselves on land-management practices such as prescribed fires, forest industry/ practices, herbicide treatments and food plot practices,” Lackey suggested. “Also, seek out advice from local county foresters, local extension agents, state private lands biologists and private forestry/wildlife consultants who can help you get up to speed and pointed in the right direction. Ultimately, given the right circumstances, landowners can be actively managing their lands to include proper forestry practices and prescribed fires.”

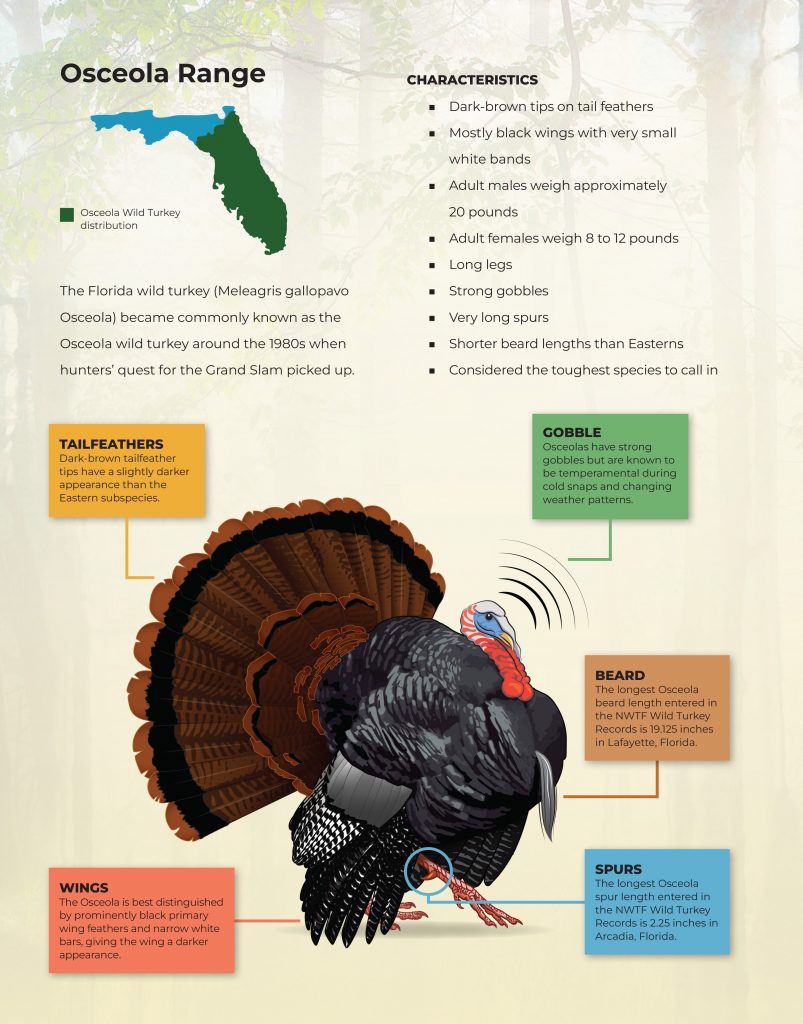

Osceola Range

The Florida wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo Osceola) became commonly known as the Osceola wild turkey around the 1980s when hunters’ quest for the Grand Slam picked up.

CHARACTERISTICS

- Dark-brown tips on tail feathers

- Mostly black wings with very small white bands

- Adult males weigh approximately 20 pounds

- Adult females weigh 8 to 12 pounds

- Long legs

- Strong gobbles

- Very long spurs

- Shorter beard lengths than Easterns

- Considered the toughest species to call in

TAILFEATHERS

Dark-brown tailfeather tips have a slightly darker appearance than the Eastern subspecies.

WINGS

The Osceola is best distinguished by prominently black primary wing feathers and narrow white bars, giving the wing a darker appearance.

GOBBLE

Osceolas have strong gobbles but are known to be temperamental during cold snaps and changing weather patterns.

BEARD

The longest Osceola beard length entered in the NWTF Wild Turkey Records is 19.125 inches, harvested in Lafayette, Florida, in 2008.

SPURS

The longest Osceola spur length entered in the NWTF Wild Turkey Records is 2.25 inches, harvested in Florida in 2014 and 1997.

The Sought-After Osceola

To an untrained eye, Osceola turkeys appear strikingly similar to the venerable Eastern subspecies, but there are distinguishable differences between them.

First, pure Osceolas feature black wing feathers with irregular white streaks, while Easterns have white wing feathers with larger black bars. Osceolas also run a bit lighter on average than Easterns. Most Easterns I’ve killed in Wisconsin weigh an average of 21 pounds, but a 20-pound Osceola is considered heavy. Most weigh about 16-19 pounds.

From my observations, Osceolas sport beards similar in length to Easterns, if a bit shorter. Adult male beards in the 8- to 10-inch range are common. I’ve noticed that spurs tend to run a bit longer. Spurs around 1¼ inches are common from what I observed during two seasons of guiding hunters.

Osceola gobbles sound similar in pitch to the Eastern’s, but they generally don’t carry as far. It could be that the bird itself is smaller. Regardless, Florida’s dense humidity and vegetation decrease the distance at which gobbles can be heard. Even on calm mornings, I’ve never heard an Osceola gobble from 400 yards away unless he was across a wide-open pasture or field with no vegetation separating us.

Osceolas often roost in live oaks, cypress and red pines, especially along creeks, rivers and lakes. Natural foods are plant material, worms, insects and even small amphibians. Midday, gobblers seek refuge from the intense Florida heat underneath shade trees along field and pasture edges.

CONNECT WITH US

National Wild Turkey Federation

770 Augusta Road, Edgefield, SC 29824

(800) 843-6983

National Wild Turkey Federation. All rights reserved.