A Strategy For The Wild, Wildfire West

NWTF and Forest Service partner in Wildfire Crisis Strategy: One-third of nation’s population lives in areas at risk.

Few would dispute that the increasing frequency of catastrophic wildfires on the American landscape over the last decade represents a crisis, a situation threatening natural resources, communities, watersheds and more.

While dictionaries often define a crisis as “a time of intense difficulty, trouble or danger,” it is also observed as “a time when an important decision must be made.”

In January 2022, the USDA Forest Service launched the Wildfire Crisis Strategy, aiming to face the problem head-on. Congress supported the initiative with a nearly $5 billion commitment.

The NWTF recently signed the first Master Stewardship Agreement with the Forest Service to help implement this important strategy. A long-time partner in forest stewardship, the NWTF brings capacity, flexibility, credibility and a conservation perspective to the partnership. Over the next decade, the NWTF and the Forest Service will invest some $50 million in on-the-ground forest restoration.

“The importance and complexity of this work means we need our partners to get it done,” said Brian Ferebee, the Forest Service’s chief executive for intergovernmental relations and the executive overseeing the agency’s Wildfire Crisis Strategy efforts.

Molly Pitts, NWTF Wildfire Crisis manager, believes the federation is a logical partner to help solve the wildfire crisis, saying “This not only affects the wild turkey. It is a national crisis.”

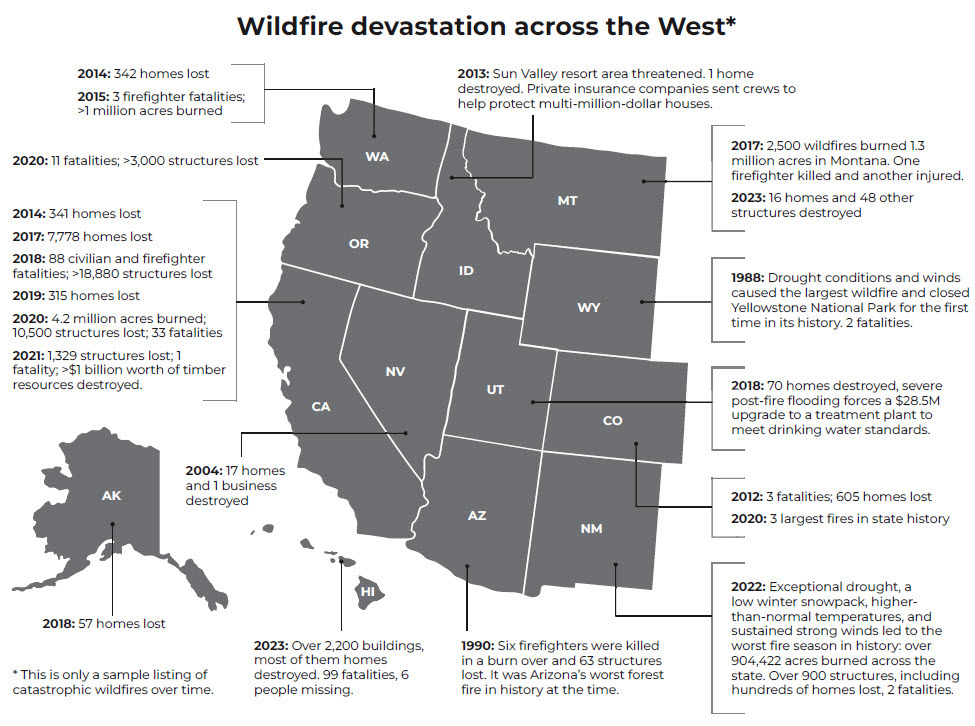

Wildfire is natural in the western U.S. Forests are dependent on frequent fire to renew and replenish. More than 100 years of fire suppression and drier, warmer weather, though, have changed our forests drastically. Today, fires are infrequent and more catastrophic than constructive.

Experts roundly recognize that fire is needed on the landscape. However, there is simply too much fuel in the form of standing dead and fallen timber and other forest debris. These landscapes must be readied for prescribed fire. Research shows that mechanical intervention in the way of timber cutting and clearing is promptly needed.

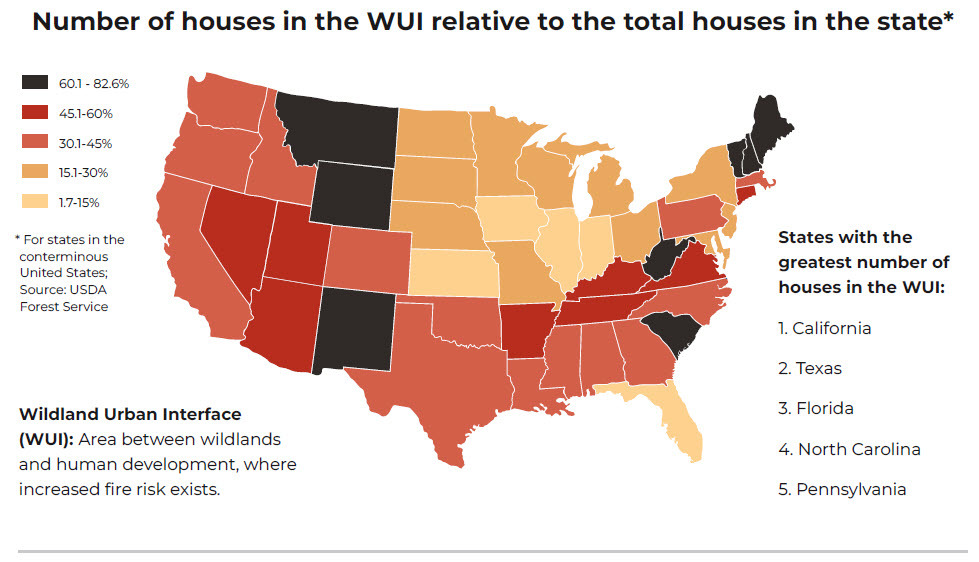

About 9% of the country’s land area is in something called the “wildland urban interface” or WUI. About 70,000 communities and one-third of the nation’s population, representing some 66 million homes, live in the WUI. The property values are estimated at $1.3 trillion. According to Ferebee, extraordinary growth in the number of people living in the WUI makes fire management even more critical and complex.

Western Wildfires Affect All

Whether you live in Montana or Mississippi, western wildfires affect you. According to the Federal Emergency Management Agency, wildfires are burning through your tax dollars and are now as destructive and costly as hurricanes. Fire suppression is also expensive. Between 1991-2000, suppression costs averaged about $550 million annually. In the last decade (2011-2020), suppression costs exceeded $2 billion annually. Tallying suppression, evacuations, property loss and recovery efforts, wildfires cost the economy upwards of $350 billion each year.

They also represent a significant cost to health. Wildfire plumes can cross entire continents. It’s not uncommon for smoke from California to reach Chicago. Smoke from Canadian wildfires last year wafted as far south as Washington D.C. Wildfire smoke carries tiny particulates and toxic contaminants like metals, carbon monoxide and hydrogen cyanide, increasing heart, lung, skin and mental concerns.

So, what does all of that have to do with turkeys? Hunting? Or the NWTF? Healthy habitats and healthy harvests.

It’s no secret that wild turkeys and other wildlife need healthy forest habitats where they can find food, water, mature roost trees, tall nesting cover, insect-rich brood-rearing areas, open areas to detect predators, an escape route and brushy escape cover. Healthy forests also just happen to offer a host of multiple benefits.

“Restoring forests restores turkey habitat, while reducing wildfire risk for communities and protecting drinking water,” explained Krista Modlin, NWTF district biologist for California, Nevada, Oregon and Washington.

A fire that stays on the ground leaves a habitat mosaic that benefits wildlife in the long term. Today’s hot “mega-fires” quickly move into the tree canopy, with some burning so hot that they create their own weather. Such fires may burn the entire forest, sterilizing the soil and destroying the seed bank. Some burned areas will not return to forests in our lifetime.

“If these forests don’t come back as forests, wild turkeys and other forest-dependent wildlife will decline,” Modlin said. “Public hunting access can also suffer. In 2020, fires closed all the national forests in California right before deer season.”

Forest management can change fire behavior. Ferebee also hopes it changes how communities experience it. That’s where the Wildfire Crisis Strategy and the NWTF come in. The NWTF is already working with the Forest Service in California and Oregon and will soon be executing landscape-scale projects in Colorado, Wyoming, Montana and across the West.

Have you ever heard, “If it was easy, someone would have already done it?”

The difficulty, decisions and opportunity needed to implement the strategy mirror the crisis itself. Reducing fuels may sound simple, but who can do the work? And what do we do with all the wood? One of the biggest barriers, identified across the country, was the loss of wood markets, infrastructure and workforce.

Moving Wood to Industry

“To get the work done efficiently, we need industry,” Pitts explained. “Industry is an outstanding tool.”

An unexpected opportunity that came with the wildfire crisis was the challenge of sustaining the wood industry as part of the solution. Can we increase results by moving industry to the wood or wood to the industry? Both increase costs. Yet both are incredibly cost effective, given that the crisis is not about the cost of removing fuels or the value of timber but rather the cost of a community, a drinking water supply or a human life.

As part of the work, the NWTF and Forest Service are testing the efficacy of moving wood to the industry, while protecting wildlife habitat, communities, water and land access, and helping underserved communities. Simultaneously, a novel company, Forestry First, was focused on an innovative approach to becoming an active partner in implementing the wildfire crisis strategy. Their idea? Reducing wildfire risk by moving wood from areas that need work but can’t use the wood to mills that need wood to sustain jobs and operations.

Fortuitously, Forestry First was concurrently making significant financial investments in rail sidings, rail cars, bunks, retrofits and debarking equipment, and investing countless hours negotiating logistics with the railroads. Literally and figuratively, Forestry First created an opportunity to get the train back on track.

This “timber transportation pilot” moved its first load of fire-salvaged logs from northern California to northeastern Wyoming by rail this spring. The logs were peeled to avoid transporting bark beetles. Then, loaded onto railcars, they left the Sierras and the communities nestled within. They crossed the inter-mountain sagebrush and arrived in Wyoming, where they were milled into wood products, as well as building materials that store carbon, removing the element from our atmosphere, through an innovative production process.

“The timber transportation pilot is difficult, complex, and sometimes raises more questions than answers,” Pitts said. “The Wildfire Crisis requires that we challenge our thinking and try new things. If we think inside the box, we trap ourselves inside the box.”

CONNECT WITH US

National Wild Turkey Federation

770 Augusta Road, Edgefield, SC 29824

(800) 843-6983

National Wild Turkey Federation. All rights reserved.