50-Year Journey: How Turkey Hunting Has Changed Since 1973

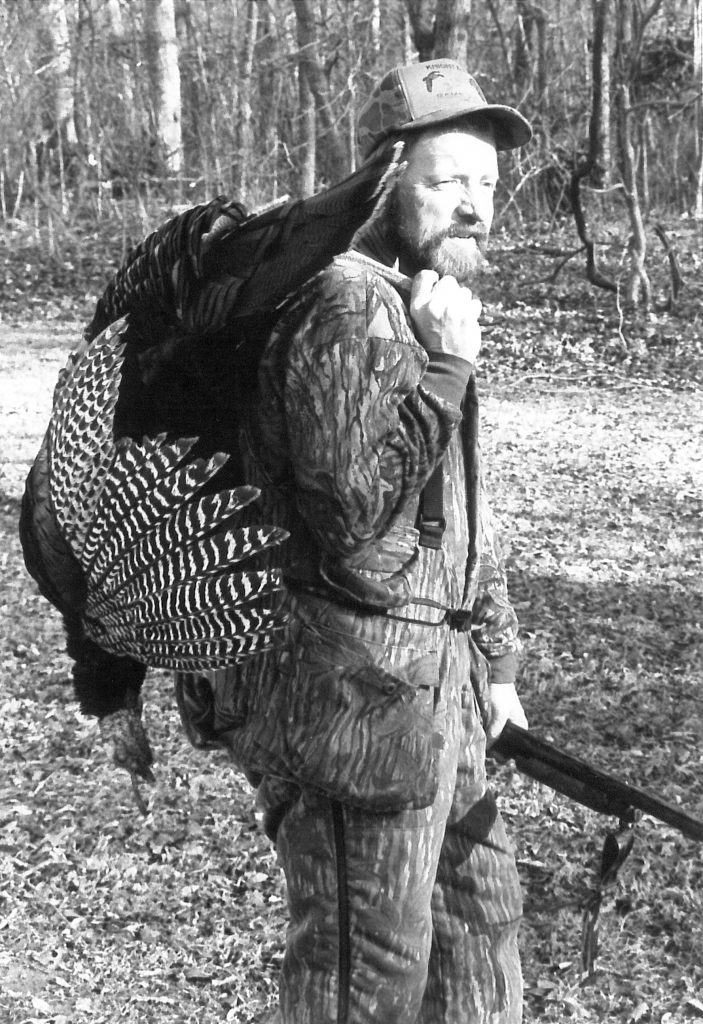

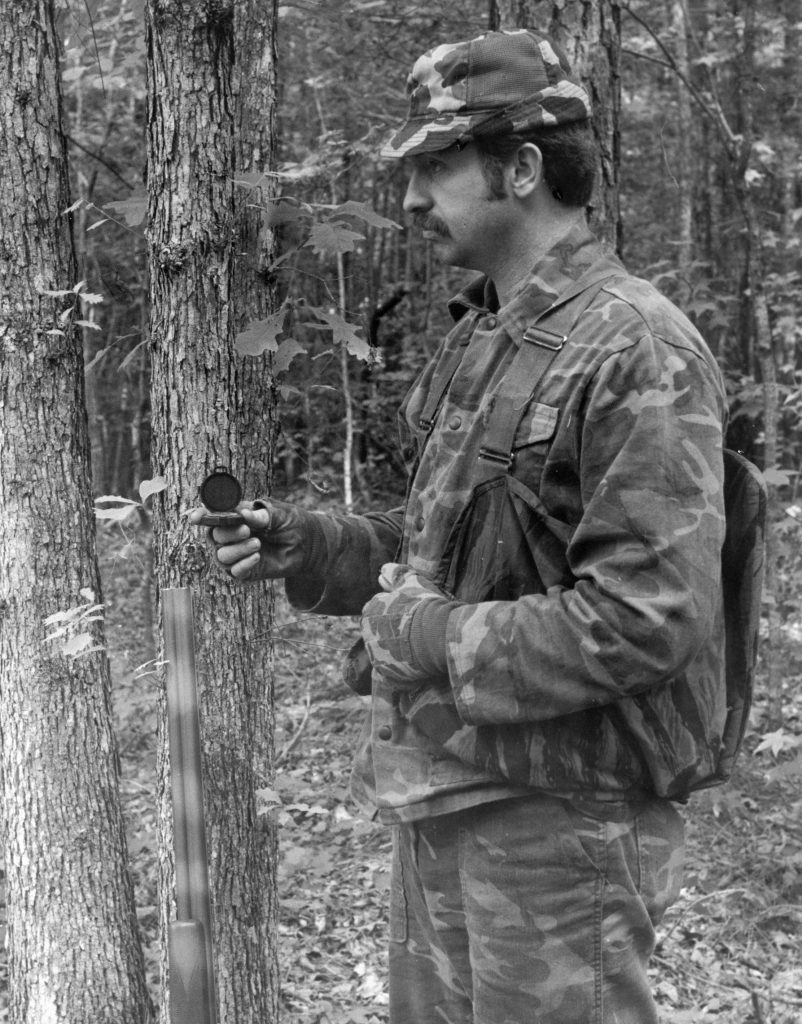

Old photos reveal another world that seems familiar at its core yet strangely foreign.

You can interpret the stories behind the images: smiling friends gather around a gobbler on a May day, or a happy hunter holds his first bird by the feet. But what about that retro clothing and those clunky-looking guns? And what’s up with those hats?

Turkey hunting looked a lot different in 1973, when the National Wild Turkey Federation was founded and began spearheading the bird’s comeback. But unless you were there, it might be difficult to grasp just how different the scene was 50 years ago and how much it has changed in the five ensuing decades.

Early Days of the Tenth Legion

Perhaps the most striking facet of turkey hunting in 1973 was the scarcity of turkeys on the landscape. When the NWTF was founded, biologists estimated there were only about 1.3 million turkeys in America, and just 22 states held a spring gobbler season. Compare that to today, with more than 6 million turkeys and seasons in 49 states. That lack of abundance, and the fact that turkey hunting was new to many folks, created a different atmosphere.

“There was a brand-new generation of turkey hunters out there trying to figure out the best way to play the game, and it was a new game,” said Rob Keck, former NWTF CEO. “There were only a few veteran experts that very reluctantly shared tactics and calling scenarios and gave out information.”

Dr. James Earl Kennamer, retired chief conservation officer of the NWTF, hunted turkeys with his father in Alabama when many other states didn’t offer that opportunity. He said the learning curve was steep, as there was little how-to advice available.

“There was no information on how to turkey hunt,” he said. “It was just learning on your own... trial and error. And you made all the mistakes.”

And, as Keck mentioned, experienced hunters often didn’t want to share their knowledge, keeping to themselves in what seemed like a secret society.

“It was a learning process,” said veteran hunter Larry Proffitt of Tennessee. “Everybody was quiet. You’d ask somebody, ‘You been hunting today?’ They’d say, ‘Yeah.’ ‘Well, how’d you do?’ But they kept it as secret as a secret barbecue sauce.”

That slowly changed as turkey populations grew and expanded, and new generations of hunters clamored for information. Keck and Kennamer said turkey calling contests, seminars and banquets attracted huge crowds of folks eager to learn. Keck remembered an event in Buffalo, New York, when more than 1,000 people crammed into a banquet hall and the fire marshal had to turn folks away.

“That was very typical of those days, the ’70s and early ’80s,” he said. “If you had a calling contest anywhere, the place was filled. People were hungry for that knowledge. Of course, that was before video and social media. Now, you go on social media or your iPhone and find whatever you want.”

Gear

The past 50 years have also seen incredible advancements in equipment, including camouflage, footwear, calls, decoys, blinds, vests and other accoutrements. In 1973, very few manufacturers catered to turkey hunters, leaving folks to fend for themselves.

“You couldn’t find any equipment,” Kennamer said. “There were no books available. It was hard to get turkey calls. I made some of my first camo by getting some brown pants and spray painting them.”

Demand from an increasing cadre of new turkey hunters soon created a cottage industry, with many mom-and-pop shops producing gear.

“Wing Supply in Kentucky started sending out fliers, and in the back of Turkey Call magazine, sometimes there’d be ads in there, and you’d buy everything you could,” Proffitt said. “The first decoy that came out, that was a novelty. It was big and heavy. If you took it to the woods and something hit it, it sounded like a snare drum. The first gobbler that saw it took off running like he’d seen a ghost. And if you had a blind, it was made with stuff you found in the woods.”

Firearms and shotshells have also seen remarkable advancements. During the early days, turkey hunters in many areas still favored rifles. Those who used shotguns often carried all-purpose models loaded with generic highbrass shells.

“Back in 1973, the choice of guns most times was a goose gun,” Keck said. “People felt you had to have a long barrel. The 10-gauge became a favorite of many, and big shot sizes were promoted. There really wasn’t any specialized turkey ammo in 1973. And unless somebody spray painted it or put some World War II camo tape on the barrel, there weren’t camo shotguns like there are today.”

Nowadays, of course, hunters have high-tech clothing, pop-up blinds, specialized turkey shotguns, custom- and CNC-manufactured calls, precision choke tubes, shotshells with heavier-than-lead shot, and apps and online resources that make finding turkeys far easier. However, Proffitt pointed out one constant.

“One of the biggest things I think is different is the technology that’s available today,” he said. “But turkeys are still turkeys.”

Looking Forward

Fifty years of turkey hunting memories can also generate substantial perspective about the future. Keck, Kennamer and Proffitt acknowledge that they likely experienced turkey hunting’s heyday in the 1990s and early 2000s, and that recent population declines in some areas have been challenging. They remain optimistic about the sport and the bird that drives it but reminded folks that we must learn from history.

“The hunt has evolved,” Kennamer said. “It’s more about the kill now than the hunting sport. That’s the disappointing part of the whole craft of learning to turkey hunt. In any sport, you want the best equipment to compete and be better than your opponent.

But when I grew up, it was the hunt itself that made the whole deal. I wanted to do it on my terms, kind of like the fly fisherman. I’m not going to have every gimmick in the world. I want to play with him on his terms and try to kill him. I think we’ve lost a lot of that in this day and time. It’s a numbers game. It’s become how many turkeys can I put on the lodge pole as opposed to why do it to begin with.”

Keck said hunters need to remain vigilant and proactive about managing and conserving turkey populations.

“I think there’s a lot of the newer generation that just take for granted that we’ve just had this forever,” he said. “We need to impart on them their responsibility to manage, support, share and to continue this legacy of what we have enjoyed now since the late 1970s and into the present time. I think that sometimes we’ve made things too easy. We live in a fast-food society, and they want instant this and instant that. They want to just go out and make it happen without paying their dues, without the experience.”

It’s difficult to speculate what turkey hunting will look like in another 50 years. The scene will certainly change. However, thanks to the legion of conservation-minded hunters and NWTF supporters, you can be sure America’s greatest game bird will continue to receive support and inspire passion like no other animal. And that alone should be reason for optimism.

CONNECT WITH US

National Wild Turkey Federation

770 Augusta Road, Edgefield, SC 29824

(800) 843-6983

National Wild Turkey Federation. All rights reserved.