Turkeys In The Watershed

Work in Arizona and the Western Wildlands is enhancing wildlife habitat, building wildfire-resilient forests and improving water quality.

What do a turkey, a glass of water and an Arizona resident have in common?

Here is a hint. This seems like a riddle, but it is an excellent illustration of the NWTF’s mission delivery. The NWTF has accomplished a lot over the last 50 years and as threats to turkeys and their habitats get larger and more complex, our conservation work must include more partners and treating larger landscapes. And that’s how the story begins, linking unlikely partners together to help heal a landscape that provides for so many different interests.

The General Springs Stewardship project exemplifies modern mission delivery and the scale of work necessary in the West.

General Springs is near Flagstaff, Arizona, on the Mogollon Rim in north-central Arizona’s Coconino National Forest. It sits in the middle of the Cragin Watershed and provides critical drinking water for the town of Payson, Arizona. The 200-mile-long Rim is characterized by impressive Kaibab limestone, Coconino sandstone and extensive Ponderosa pine forests. Ponderosa pine forests like these drive NWTF’s forest restoration work in this area.

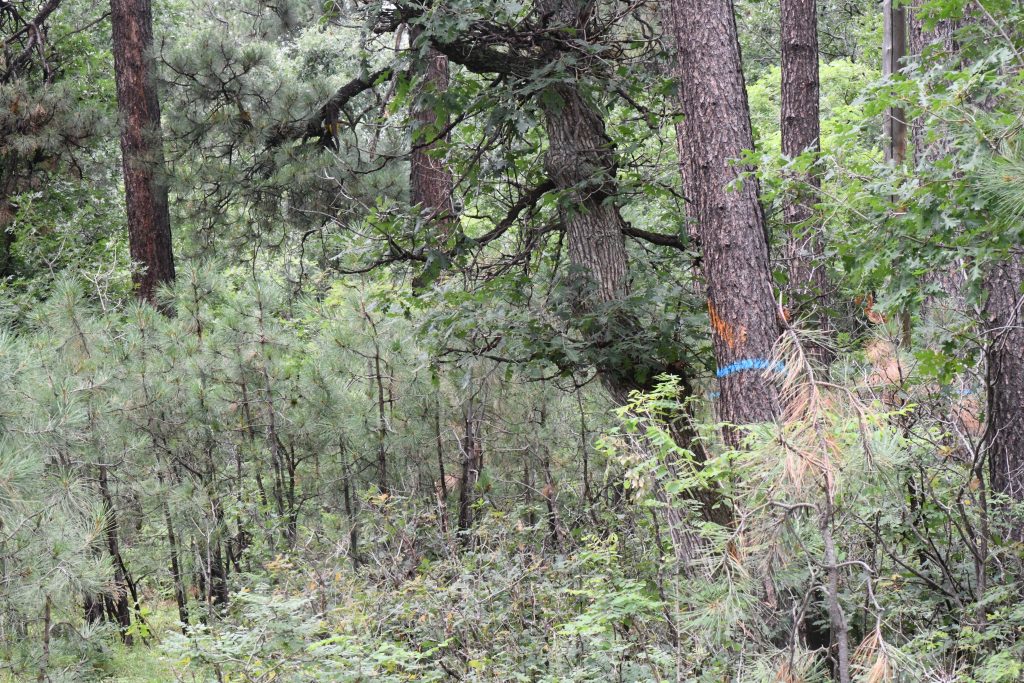

“These forests are super thick,” said Chuck Carpenter III, the NWTF’s district biologist for Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico and Utah. “There are too many stunted trees instead of a healthy, diverse forest providing good turkey habitat. Turkeys need forbs, shrubs and soft mast, and they need a forest floor they can run across to avoid predators.”

The health of Western ponderosa and other dry pine forests has been declining for decades. The causes for the decline are many, deeprooted and interrelated.

Cause for Concern

The chief cause was several small fires in one of the driest years on record that changed history. In June 1910, the woods were ablaze in Idaho, Montana, Washington and British Columbia. In August, that same year, hurricane force winds drove fire across 20 million acres of forest, killing 86 people, most of them frontline firefighters. What later became known as the Great Fire of 1910 also burned a deep and long-lasting scar on Americans. It fundamentally shaped the USDA Forest Service and national fire policy. Fire was a four-letter word, and we wanted it removed from the landscape.

Fire may still be a four-letter word, but we realize today it isn’t always a bad word. Many forest types (and wildlife) in the West are fire adapted or fire dependent. In the current condition, however, few forests are ready to receive fire. More than a century of fire suppression has changed the forests’ vegetation structure. Frequent, low-intensity fires used to burn through savanna-like forests, reducing fuels on the forest floor and rarely making it into tree crowns.

“Now, in addition to large trees, grasses and forbs, we have a lot of medium-sized trees and large shrubs, or ladder fuels that carry flames into the crowns,” explained Linda Wadleigh, the Mogollon Rim District ranger. “These uncharacteristic crown fires affect all the values: wildlife habitat, drinking water quality, access for recreation and public safety.”

According to Wadleigh, fire behavior is dependent on weather, topography and fuels.

“We can’t change the weather or the topography,” she said. “The one thing we can do is remove ladder fuels to reduce the risk of uncharacteristic crown fires.”

The Mogollon Rim has seen its share of large, uncharacteristic crown fires, dubbed megafires: the 2002 Rodeo–Chediski fire burned 470,000 acres, and the 1990 Dude fire burned 30,000 acres and killed six wildland firefighters. Yet, its ponderosa pine forests remain at risk.

"If a forest is destroyed by an uncharacteristic crown fire, you will not see that forest again in your lifetime. We cannot sit by and watch. We need to act."

Linda Wadleigh

Mogollon Rim District Ranger

Becoming Resilient

Today, forest resilience, not fire removal, is the goal. Fire will be ever-present on the Western landscape. Resilient forests withstand disturbance. Fire won’t dramatically change their composition or function.

A complex problem requires a multi-pronged solution. With today’s elevated fire risk, working at an increased pace and larger scale are crucial. For the Cragin Watershed at the center of this stewardship work, the right scale is treating 31,000 acres across the entire watershed. With partners, the NWTF is tackling the first 3,519 acres and the Arizona Department of Forestry and Fire Management is confronting another large piece.

The Salt River Project is a key partner in both projects. This project is a not-for-profit water and power provider for 2.5 million people in the greater Phoenix area. General Springs is the SRP’s number one priority in the Cragin Watershed, containing the CC Cragin reservoir and dam, as well as SRP powerlines, the town of Payson’s water pipeline and other infrastructure.

For the SRP, unhealthy forests put the entire watershed at risk. Elvy Barton, the forest health management principal for SRP explained, “These mega-fires can devastate a watershed. They increase sediment and decrease water quality for our customers. Post-fire flooding is dangerous to people and infrastructure, like dams and pipelines, and sediment flows into our reservoirs, reducing storage capacity.”

The West’s water needs are dependent on dams and the water stored behind them in reservoirs. Ash, debris and other sediment flooding into a reservoir is like filling up a bathtub with mud. More mud in the tub leaves less room for water.

“Reducing wildfire risk is more effective and efficient than building new reservoirs or dredging old ones,” Barton said.

“Today’s wildfires are massive, and it’s important to be proactive versus reactive,” Carpenter added. “Being reactive costs way more money, it’s worse for wildlife and way worse for the watershed.”

When it comes to being proactive, Barton agreed: “Letting it burn is not an option. Why risk people’s lives, livelihoods and water when we can reduce burn severity and lower that risk?”

A human characteristic we all share is that we tend to view things in snapshots, as if our memory or perspective of a place is how it always will be. In reality, life and forests are not static. They are always changing.

“If a forest is destroyed by an uncharacteristic crown fire, you will not see that forest again in your lifetime,” Wadleigh said. “We cannot sit by and watch. We need to act.”

Note: Patt Dorsey is the NWTF’s director of conservation in the West. She lives in southwest Colorado, about five hours from the Mogollon Rim.