Seek the Road Less Traveled

PSA to hunters: To encounter more birds, research suggests putting your walking boots to work.

“Are you seeing any birds?”

That is certainly one of the most common questions turkey hunters ask of themselves and their friends each season.

The probability of our favorite scenario, namely a hunter happening upon a turkey in the woods is, by all accounts, pretty amazing. After spending the better part of my professional career and quite a few personal days chasing birds in the woods for fun, I’ve always been interested in the driving force behind wild turkey movements in the wild.

I have always felt that hunting success each spring came about from a mix of skill, luck and random chance. Neat technological advances for tracking wild turkeys, combined with people willing to lug around GPS units for research projects, are yielding amazing insights about how turkeys act when hunters hit the woods.

So, I’m taking a different slant in this issue by looking at research related to how turkey hunters move and how turkeys responded.

How Turkey Hunters Hunt

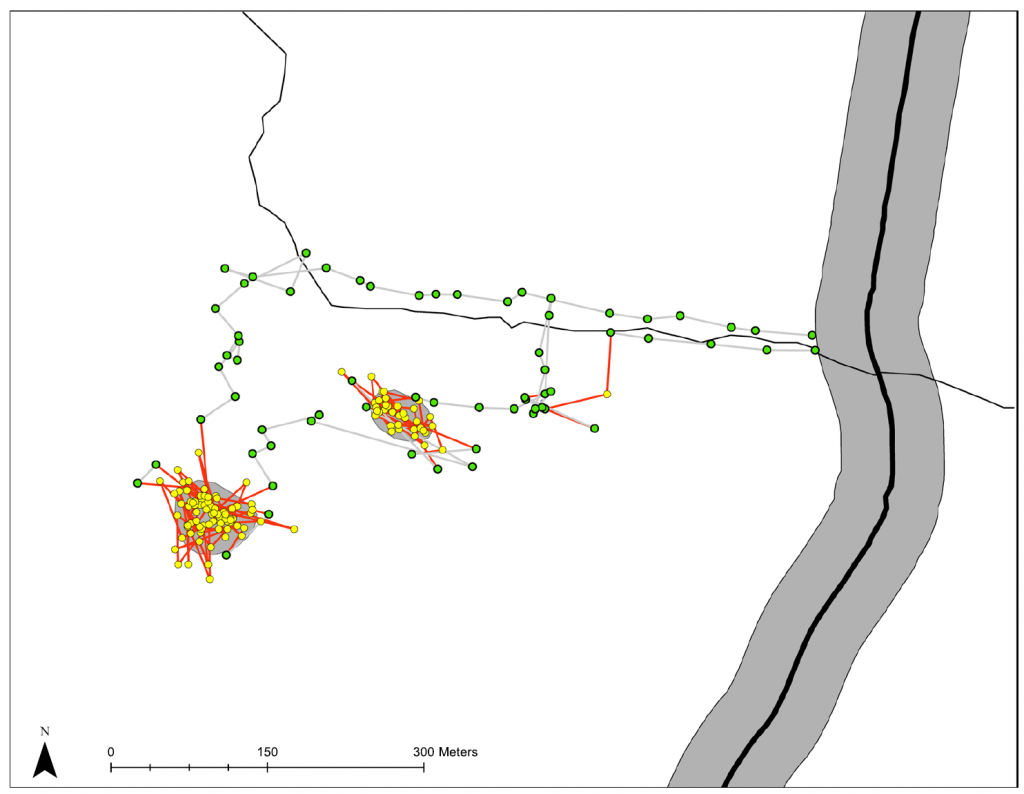

Turkey hunters are an interesting lot. We can generally classify turkey hunters into two groups: the sit—and-wait hunter and the run-and- gun hunter. Our understanding of turkey hunter movements, however, has historically come from surveys, asking hunters how long and where they hunted. One of my graduate students, Alaina Gerrits, put global positioning system tags on male and female wild turkeys and requested hunters carry GPS tags while hunting on the Webb Wildlife Management Area in South Carolina. The intent was to examine hunter-turkey interactions. We were not disappointed!

The Roads Most Travelled

Here is how it went down. First, we tracked some 175 male and female wild turkeys over four years. About 1,500 hunters carried GPS units while turkey hunting on the WMA. We found considerable variation between individual hunters as they moved in the woods. The first thing we learned was that turkey hunters love walking roads that don’t allow vehicle traffic, especially maintained roads and paths used for management activities such as timber harvest or as fire breaks. We called these “secondary roads” in our study.

We all know that turkey hunting is mostly a morning sport. Most hunters hunted about four hours each morning and were out of the woods by 10 a.m. As expected, hunters spent a lot of time working secondary roads, with 40% of all hunter activity occurring within 25 meters of the roads. Most hunters set up to call and hunt within 100 meters of the roads. Interestingly, hunters spend about the same amount of time moving (54%) and stationary (46%). When they move, boy do they move, covering about 60 meters a minute. That’s an average of about 2,100 meters for each day of hunting.

Hunting bouts, or the movements and stationary activities of a hunter, are interesting to see and reveal much about hunter activity, including location, distance and speed.

Turkeys Respond

How hunters move is interesting, but even better, Alaina’s study gives some insight to how turkeys respond to turkey hunters.

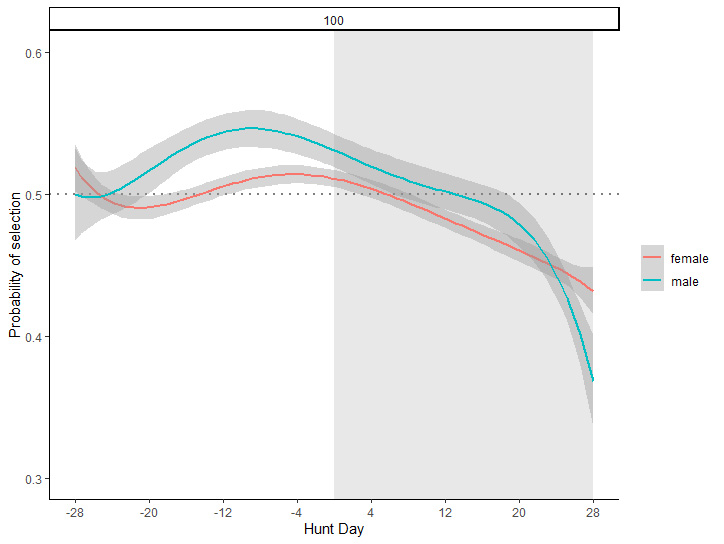

First, when a hunter enters the woods, they become part of the predator-prey equation. We expect to see wild turkeys respond by making behavioral adjustments in their day-to-day activities. The big question we had was, “How did wild turkeys respond to all those hunters on the landscape?” The answer: rapidly. The results couldn’t be clearer when we plotted it out. When hunting season began, male wild turkeys showed an immediate and strong response to hunting activity by leaving areas near secondary roads they had been using before the season started. The response was slower and not as strong for females.

Interestingly, the response strengthened throughout the season. This is something we did not expect. We thought that after the first couple of weeks, hunter density would decline (it did) and turkeys would respond in kind (they did not).

Another interesting result from Alaina’s work is that while turkeys responded to hunting activity by shifting their ranges, they did not change what habitat characteristics they used; they just moved off into another area within their range that was farther from heavily used areas.

I guess the easiest take home from this research is that hunters should search for those paths that are the least taken. I expect turkeys will be at the end of them; if not, then hunters can at least enjoy the beauty of the forested and rangeland ecosystems our state wildlife agencies manage for wild turkeys now and into the future.

Tracking Hunters:

- 4 Hours hunters spent in the woods

- 10 a.m. Average time hunters left the woods

- 40% Percentage of hunter activity within 25 meters of WMA secondary roads

- 54% Percentage of time hunters were on the move

- 46% Percentage of time hunters were stationary

- 2,100 Meters the average hunter moved while hunting

Data from 1,500 hunters outfitted with GPS units while turkey hunting South Carolina’s Webb Wildlife Management Area