LPDV and Is It Cause for a Population-Level Concern?

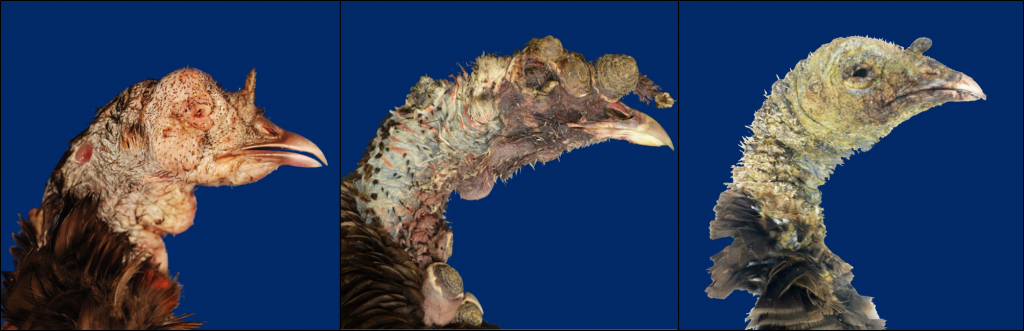

It happens to turkey hunters throughout the country; they harvest a bird that they thought was tired and beat up from scrapping all spring, but upon a closer look, the bird’s head and feet are covered in thickened skin, bruising and discoloration.

This is a key indicator that the wild turkey may be infected with lymphoproliferative disease, or LPDV for short.

LPDV is caused by a retrovirus and was first documented in domestic turkeys in Europe and Israel in the 1970s. In 2009, the disease was documented for the first time in wild turkeys in Arkansas and has since been observed in at least 29 states as well as Canada.

Some infected birds form tumors in their internal organs and skin and may exhibit many other side effects, like weakness and lethargy, while some infected birds display no noticeable clinical signs but may experience more insidious effects, such as decreased immune system health and secondary infections (such as with poxvirus). Though the disease can be detrimental to individual birds and many basic questions about the disease still remain, even less is known about its effect on wild turkeys at a population level.

The South Eastern Wildlife Disease Cooperative Study states high LPDV prevalence has been concomitant with population declines in wild turkeys in the midwestern and eastern United States.

Research to understand more about the disease and its potential to have an effect on a population level is currently underway. The NWTF is helping fund a project led by the SCWDS at the University of Georgia that will utilize state-of-the-art technologies to study diseases at a cellular level, informing the overall understanding of disease ecology and helping guide future wild turkey management.

“Our primary objective is to determine where and to what extent LPDV is distributed throughout the body of infected wild turkeys, including comparison among turkeys that have no evident disease, those that have mild disease and those that have severe, fatal disease, such as those with multi-organ lymphoid tumors,” said Nicole Nemeth, D.V.M, Ph.D., associate professor at the University of Georgia. “This will be accomplished through the adaptation of an existing, advanced diagnostic tool for LPDV and for a similar, tumor-causing virus that also circulates in wild turkeys, reticuloendotheliosis [REV] virus.”

The team is examining LPDV and other diseases within cells and tissues of wild turkeys and assessing patterns of how these diseases spread and how they manifest in a variety of circumstances.

Nemeth and her team are utilizing the emerging capabilities of the RNAscope. The technology allows users to examine the distribution and extent of virus components within both diseased and non-diseased tissue at a cellular scale. Researchers will develop this technique specifically for LPDV and REV to not only study single virus infections, but also co-infections with both viruses.

To this point, due to limitations in currently available diagnostic tools, it has been impossible to distinguish the extent of LPDV and REV infections in cells and tissues (because both viruses can cause similar lesions), and through the RNAscope’s technology, the team will get a clearer picture of how widespread and damage-causing these viruses can be in birds at various stages of infection and disease.

Data attained from the lab findings will be compared to field data from multiple Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study member state agencies and will help better gauge the population-level effects of LPDV on wild turkeys and what management strategies could be implemented if needed. For instance, findings could provide a better understanding of how LPDV may affect wild turkeys' reproductive success.

“We need to answer these basic questions at the cellular level to understand their effects on host fitness and extrapolate to potential population-level effects,” Nemeth said. “This information is crucial to understanding mortality investigations and field study findings, such as reduced fecundity in ongoing and future LPDV and REV studies. This research will fuel future studies aimed at the overall goal of wild turkey conservation and management given the importance of turkeys as a gamebird.”

Samples for the research project will include birds from multiple states throughout the Southeast as well as from experimentally infected turkeys to use as a comparison with naturally infected turkeys.

If you harvest a bird that you believe is infected with LPDV, be sure to report it to you state wildlife agency.

(An earlier version of this article stated that findings from a variety of research groups across numerous disciplines suggest high LPDV prevalence could be associated with population declines in wild turkeys in the East and the Midwest. That statement was changed to: The South Eastern Wildlife Disease Cooperative Study states high LPDV prevalence has been concomitant with population declines in wild turkeys in the midwestern and eastern United States.)